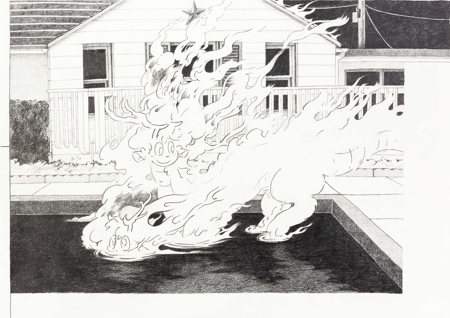

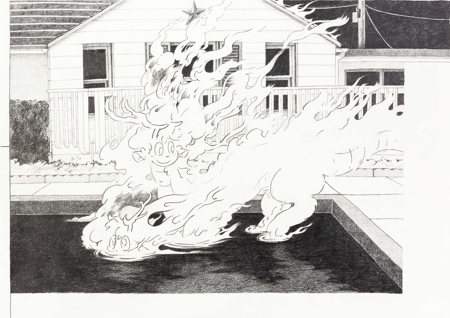

In American Evening,[1] a large drawing from 2017 by Paul Peng, a flaming dragon boy gallops into an inground swimming pool. We see the central character simultaneously at two points in his descent. In one, his paws have only just made contact with the surface of the water, and blinding white flames trace the proud arc of his back. In the second, only his eyes break the tranquil surface. He is nearly extinguished.

The pool is not his. The house the pool is attached to is ablaze, evidently unfit to house a beast that burns what he touches. At the same time, nobody is disrupting the dragon’s rampage. It’s night and the windows are graphite black. The dragon twists his attention from the edge of the pool to the pool’s far end. He is focused on his movement and nothing else. no offscreen parties or additional factors complicate the action.

This is an especially important distinction to make with Peng’s work, as an artist who will frequently create scenes suggesting auxiliary media that does not exist. In American Evening, for example, he frames the image in a slight grid, one that suggests a metafictional print layout that this image has been extracted from and reproduced in the completed drawing, suggesting an authored narrative beyond the scope of the original image even when none exists. So, this is a scene with one character, one who may wreak havoc but is acutely aware of his surroundings and is intimately in control of his functions.

Peng has a number of pieces like this, characters seconds away from extermination, aware and enthusiastic of their fate. The pooltoy has appeared throughout his broader body of work, a permanently rapturous, excruciating delicate symbol of leisure, ascribed as a bottom at the moment of its production.[2] In his work, Peng will often depict instances of pooltoys in precarious situations, or even at the exact moment their glossy, taught surface is punctured by a foreign object. An obvious instance of this, titled Pop,[3] was shown at the Anthrocon art show in 2025, in which the moment of rupture itself is anthropromorphized as a knowing, smug, unblinking oracle operating on physical principle but wholly privy to the sexualized context in which it performs.

Despite this, Peng never depicts the carcass of the beast, the pooltoy crumpled into a wreck of plastic, or anything else of the sort. It’s the instant of destruction that enraptures him, in a manner similar to the religious fanatic and the doomsday prepper. Peng imagines a million scenes of rapture parallel to each other, boys who are remembered for the moments of their collapse more than any of their attempts to act on their own subjectivity.

Though, this all could be said of pornography more generally. What makes Peng’s work special aside from his attempts to code these ruptures into metaphor? Well, the closet certainly is a central aspect of Peng’s work. American Evening was shown to the public as part of Objects of Virtu, an IRL group show at the Pittsburgh-based art gallery Romance in 2023. In the press release for this show,[4] Peng’s stock cast of sex beasts are described as “faintly erotic furry-adjacent DeviantArt characters,” wording that I can only imagine came from Peng himself, or from an interview with him circa 2023.

Within two years, Peng’s characters went from being “furry-adjacent” to co-curating Room Party, the “first-ever large-scale group exhibition of contemporary and experimental furry art,” hosted at Bunker Projects (also in Pittsburgh).[5] What changed? I’d argue not much.

Even in his sizable body of work that could be considered abstract, Peng employs a mode of self-negation identical to his figurative drawing. For example, in 2018’s Versace (Reverse),[6] Peng employs another composition that suggests the existence of a longer comic that has been withheld. We see a warrior boy. He wields a hilt that resolves into no sword and a shaft that resolves into no penis. Peng intentionally withholds narrative resolution in service of a broader metadrawing, with the final image, despite the obvious craft behind it, being relegated to the status of a partial document, even as it engages the viewer aesthetically.

This work is, invariably, in dialogue with pop art, and the broader history of the readymade. For as long as there has been mass media, there have been anonymous objects, ones that could be carefully re-authored in the manner of Duchamp. The worst art downwind of Warhol (the most famous artist born in Pittsburgh) treated mass media images as natural resources ripe to be plucked and packaged for white aesthetic consumption. In America, where I currently live, a substantial share of these objects are made in Asia, often China, and packaged as the work of a brand, or of nobody at all, something that grew, like how leaves grow off a tree.[7]

We can think of Duchamp superfan[8] Christian Marclay’s manga collage paintings, how he simply “became aware of manga” on a trip to Japan,[9] and how that can be considered substantial by institutions curated to assure his success, in the style of the painters that trawled the globe’s fertile soil before him (Gauguin, Ingres, etc.).

Through Peng, we are asked again to consider who made the readymade, and what it means when an image is culturally ubiquitous. Peng begins by creating a finished assemblage, where information has not been removed but instead withheld. The burden then falls back onto the viewer to reset the balance of nature, to resolve the image into its metafictional constituent parts. Peng inverts the relationship between manufacturer and product and smuggles his own subjectivity into a mechanical language of imagemaking.

But there’s more going on than just that. Peng obviously finds some erotic pleasure in this mode of depiction, reproduction, and commodification. Again, a pooltoy is a bottom made in a factory. We can see Peng’s negative spaces, too, as images suppressed, brought to life in flights of fancy and then erased. It is tempting to say here that Peng is getting away with something, same as every other furry working in contemporary art right now, that this mode of drawing may be considered new and exciting to regional galleries only because the curators have not yet caught on that it’s pornography, and that when we are pulled out of the closet, a small handful of us will be canonized as artists, and the rest will fend for scraps, as was the case with the mangaka and the leather freaks and the drag queens that proceeded us.

Oh what a valley of contrasts! Lol. As of August 2025, furry is relatively lame and unprofitable. We have a few guys in our camp who are threatening to break through to the big leagues, but not in a way where any of them are able to comfortably afford rent. Mark Zubrovich was doing a flash sale on their Insta story the other day because DOGE was cutting off his SNAP benefits.

At the same time, furries are on the Pinterest board of every major studio releasing media with talking animals in it.[10] The weak, those contemporary artists who cashed in on furry imagery as shock value in the 2010’s, have largely moved onto other things. Michael Pybus hasn’t had a solo show in two years. Jamian Juliano-Villani got bored scalping imagery off tf fetish blogs.[11] Our scene feels ripe, ready to burst. How will we, the furries, protect ourselves from the same fate that befell the subculture weirdos that came before us?

Well, we probably won’t, and it’d do us good not to get too precious about it, but that’s only half the story.

"While the unease Fried felt when viewing a Tony Smith sculpture is a feeling he doubtlessly experienced as sheer terror, it was not the well established sensation the subject experiences in realizing that the object gazes back. Instead it was an instance of dissociation. Fried was not extorted into a situation with a Tony Smith sculpture which returned his gaze, in truth his experience was a dissociative vision of seeing himself seeing the Tony Smith sculpture."

To talk about Room Party, and the tantalizing narrative of furry art more broadly finding purchase in the art gallery (which I promise I will do eventually), it is necessary to establish its less discussed, but equally important, parallel thread, that being contemporary art’s concessions to the mechanisms of fandom.

Bill’s PC is some sort of arts thing based in Western Australia that opened in 2023, the same year as Romance. When it opened, it described itself on its website as an “artist-run exhibition program with a physical location.” It now refers to itself as simply a “gallery.” This minor shift in nomenclature is essential to what I’m talking about here.

Bill’s PC is essentially a closet in a basement on property that is twice removed from the ownership of curator Matt Brown. Even ignoring the space’s distance from the West’s canonical art centers it takes some careful planning to see the space in real life at all. According to Bill’s PC’s website, the space is situated between two different numbered addresses and is only available to view “by announcement or appointment.”[12] If this were a strictly physical artist-run space based in a loft in 60’s Western Australia, it’d be next to impossible for most interested parties to see the work in question.

However, let’s consider the name of the project, “Bill’s PC,” the fictional filesharing service that allows Pokémon to be stored and transferred instantaneously across arbitrary geographic distances. Bill’s PC, as much as it is a Perth gallery, is a computer gallery, one that can be accessed by a select few physically, but through appealing documentation, rigorous social media curation, and wordofmouth advertising, became a physical space with much more relevance to computer dwellers than any Perth art institutions.

But it’s not just a blog, right? Anything that can be concretely said to have “happened,” be it a tree falling in the woods or a show opening attended by nobody, attains a sort of cache in our fraught informational landscape. It is a step beyond conceptual art, it is an entire conceptual gallery. It’s how I can claim to be a fan of Bill’s PC despite me living most of my life on the opposite side of the world.

Bill’s PC follows in a modern tradition of DIY art spaces codified in the the 10’s by Joshua Abelow’s Freddy (formerly Baltimore, currently Harris) and maintained by a mutating number of upstart art somethingorothers, such as Apartment 13 (Providence), rubbish bin (Berlin), stadium projects (Guelph), so on. Word of these spaces’ activities circulates between an ingroup of knowledgeable curators, but they are not particularly elite, and they are certainly not set to profit exorbitant sums from showing this work. The work in these spaces is often unusual, unpretentious, and unmarketable. We can place Bill’s PC, being paradoxically obscure and accessible in both location and programming, at a nexus of this wave of oddball art curation.

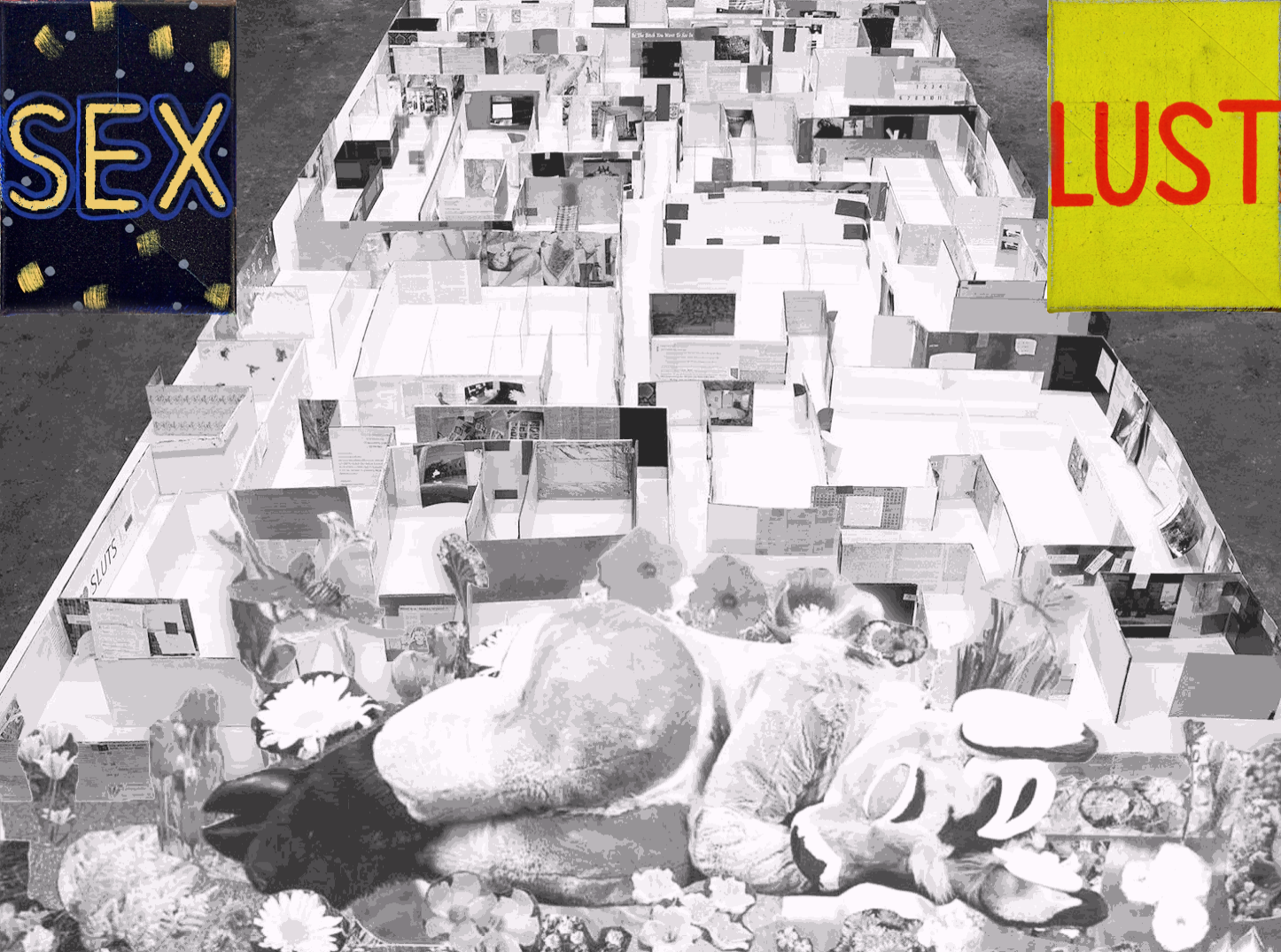

This model of distribution is illustrated well in Sylvie Hayes-Wallace’s piece Center of the Universe,[13] presented in 2022 by Bad Water, another relatively remote artspace (this one’s in Knoxville). Here, Hayes-Wallace imagines an Armory Show for clutter. The viewer (presumably) looms(ed) down over a model of a maze whose walls are adorned with all sorts of detritus, porn, trash, receipts, scratchnotes, whatever else, all level in scale atop the gallery’s dirt floor.

Hayes-Wallace is obviously responding to our internet’s glut of information, standard fare, but pay special attention to us, the viewer. When we are presented with the layout of a maze on a piece of paper, it ceases to be a strictly aesthetic object. The schematic partially becomes a game. To engage with Center of the Universe beyond a surface level, we must imagine ourselves to be small and to be in the maze somewhere, or in other words, we must imagine ourselves as the rats absent from their maze. We are (presumably) encouraged to imagine what “being there” would be like, even while we are there, even while this is the realest this space will ever be to us, the same as how I’ve never been to Noxville, Tennessee, but I’m still working to imagine myself now as a careful attendant of this show. The effect of viewing Center of the Universe on the computer is the same, but doubled, as viewing it in real life.

For a more concrete example, let’s consider Bill’s PC’s restaging of Puppies Puppies’ Condom Filled with Spaghetti,[14] itself a recreation of a viral image that entered the artist’s radar by chance via Imgur. This work is a straightforwardly Duchampian[15] readymade in some regards and not in others. Condom Filled with Spaghetti simultaneously attains physical purchase over the funny idea presented by the Imgur image and reattains its source images’ memetic qualities by restaging it in a space so intimately invested in its own metadata. Puppies Puppies did not make a sculpture of a meme and put it in a gallery, she successfully proliferated a meme through a gallery setting, or as Dispatch Review's Francis Russell puts it, “a kind of fan fiction.”[16]

This means of distribution is fascinating but is also not at all unique to our current circuit of boutique artist-run spaces. Moreso, these curators are conscious of the way contemporary art circulates through the internet, as urban legend, and are exploring the possibilities that arise from this data-centric art economy. In a practical sense, most of us are making work for Instagram first and our stated projects second.

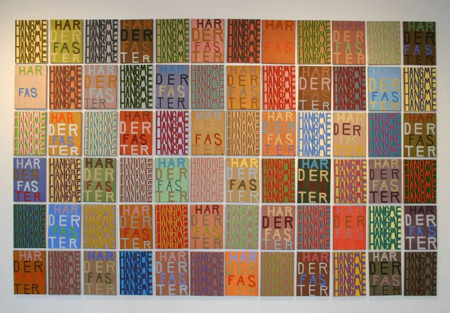

Let’s return to Joshua Abelow, an influential figure in the last three decades of American underground art. Abelow first garnered attention for his personal painting practice. His 2007 show Mystic Truths, completed while he was still in college, consisted of 72 colorful text paintings, 36 of which read “HARDER FASTER” and the other 36 “HANGME,” arranged in a checkerboard grid.[17] See: Corrections (10/15/2025)

In Mystic Truths, we can identify several staples of Abelow’s mature practice: systems-based painting, puns, cryptic messaging, and arrangements that draw attention to each individual painting’s placement in a larger body of work. He assigns himself tasks and displays the work such that the conditions of their production are obvious to the viewer, but in between these two points where he voids his subjectivity, he’s able to get a lotta real messy hands-on painting done.

If it wasn’t already clear, Abelow paints a lot. Keith J. Varadi, curator of Gene’s Dispensary in Los Angeles, quipped earlier this year, “Joshua Abelow has made more paintings than anyone I’ve ever known. He’s also destroyed more paintings than anyone I’ve ever known.” This was accompanied by a slideshow of photographs taken years apart showing dozens of paintings by Abelow piled, slashed, mangled, or otherwise placed out for disposal.[18] Seeing these images, the “HANGME” paintings in Mystic Truths assume an even more directly anthropomorphic quality. The paintings are playing out a desperate metatext in the gallery space. If they are not bought and housed by mildly wealthy patrons of the arts, they are at serious risk of annihilation. They will either be hung or hanged. They, too, are leaping into Peng’s inground swimming pool, begging to be extinguished.

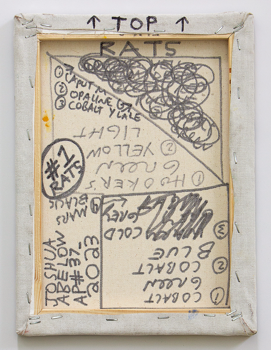

In his mature practice, Abelow generally does not mix his colors, preferring to paint with colors as they appear fresh out the tube. However, he maintains meticulous notes on these colors, how they interact with each other on his chunky, burlap canvases, which paintings he has made, and which ones he has not.[19] Most of his canvases are marked on the back with the exact steps that were taken to produce the work. When Disneyland, Paris, another West Australian artist-run space, hosted a small show of Abelow’s work in 2023, they went as far as to photograph the backs of these canvases as part of their official documentation.[20] To my knowledge, the backs of these works were not shown at all as part of the actual exhibition. This is a step beyond what we talked about earlier with Bill’s PC. People who actually went to see Joshua Abelow’s RATS at Disneyland, Perth would be able to see views of the show they wouldn’t have been able to see in person by viewing auxiliary documentation of the show online after the fact.

Besides Instagram, this strange state of affairs is enabled by the rise in popularity of websites like Contemporary Art Library, a free to access database of post-millenium art happenings. Anyone can submit either themselves or their own projects to site admins for consideration, also for free (with a recommendation for a suggested donation).[21] Clicking on Joshua Abelow’s profile on Contemporary Art Library reveals a sleek (read: abridged) archive of his activity dating back as far as 2006, including curatorial activity and placements in group shows. It’s like e621, but for paintings instead of gross sex.

Across thirty years, Abelow has maintained and expanded the scope of his painting systems, resulting in a kaleidoscopic output rich with symbolic meaning, with some of his recurring character disappearing for years at a time before suddenly returning in new, surprising ways. He’s found success in selling smaller works in larger quantities. I saw two of his small burlap diagonal paintings up for sale at Ethan Cohen earlier this year for $2000 each, a price point accessible for any moderately well-to-do patron of the arts, especially for works that feel so canonical to Abelow’s well respected body of work. See: Corrections (10/15/2025)

We can map Abelow’s reflexive, humorous, and, I’ll say it, extremely autistic body of work alongside a number of canonical art historical figures. He personally cites the influence of Ross Bleckner, who he worked as an apprentice for for a number of years, as well as Bruce Nauman, because it’s hard not to be influenced by Bruce Nauman right now.[22] He’s sort of a minimalist, he’s sort of provisional, he’s sort of this and that. For my money, more so than any of those guys, Abelow finds a closer aesthetic twin in the guys on FurAffinity who draw hundreds of nearly identical scenes of different cartoon characters getting stuck in mud.[23]

I am not suggesting that Abelow has mimicked a furry art practice or vice versa. They were simply on the same bus and got off at the same stop. Abelow rose to the front of the American arts underground because he was able to successfully square his artmaking practice into his shifting media landscape. The information in his paintings is as blunt as it is dense. His symbols accrue value through their repetition, either by him, or through their proliferation online. His work is of the internet, not about it. It worries me, with all this in mind, that the aspirational American art practice, with sellable work and relatively high institutional backing, following decades of reinvestment in the market, yields, like, at most a middle class lifestyle.[24]

Here’s a frustration I’ve had with art criticism for a while: allegedly, once these works are brought into galleries, they are quenched. The grand narrative pitched here is that our society’s increasingly secularized artists are in an arms race to scavenge for work that can impress an increasingly jaded audience strictly along the lines of form or novelty. “Wow! That probably took a long time to make!,” or, “wow! Furry porn in an art gallery? That’s weird!” The model of the gallery proposed by this line of thinking is a prescriptive apparatus, one that enforces a dichotomy between authentic and inauthentic frenzy, or in other words, between man and nature.

In reality, ideas only gain power through replication, and each dumb object in our lives contains the history that produced it.

So when our hardball critics end up actually enjoying current work, they get sheepish, nervous to be affected in a base manner, confused as to whether they are man or animal. A particularly (though not uncharacteristically) embarrassing recent video by The Yearbook Committee, an IrateGamer-esque fixture in the current fine arts world,[25] documents his first physical encounter with the work of Nancy Holt, who he first introduces as Robert Smithson’s wife.

We can see the bones of the video he wanted to make (its living history) in his discussion of the pre-Columbian Earthworks created by Hopewell civilizations in what we now called Ohio. He clearly wants to lay out the dichotomy we've already addressed that divides authentic and inauthentic art practice. Holt was clearly set up to be the academic soyjack to the chad, inscrutable artisans of the savage American West.[26]

And yeah, if Holt’s work sucked, the video would be a lot more coherent. It’d have a setup and payoff, like a knockknock joke. He all but openly admits in the video that he wanted to disparage Holt’s work. His words are, “I was ready to come here and not like this work, but despite my best efforts, I’m having an aesthetic experience,” a different type of joke than the one he wanted to tell, a self-deprecating joke, one that conveys a real sense of disorientation in the comedian.

Across a truly fascinating several minutes of video, we see The Yearbook Committee[27] move between the two large scale Holt installations housed in the Wexler Center. During his encounter with Heating System, he maintains a detached air, conceding that the work contains aesthetic and conceptual value. With Electrical System, though, something snaps in him. He asks a guard, “can we walk through here?,” and when he’s given permission, he slowly strips free of his human clothes. He bounds through the network of tubes and bulbs with reckless abandon. He hunts for interesting vantage points, he’s giggling and smiling. Some would say he’s scurrying. “It feels like a kid on Christmas. It feels magical. It feels like you’re a kid bopping through the playground of whatever.”

His visit to the Wexler ends on a strange note. Desperate to reconfigure his critical apparatus, The Yearbook Committee detours to a sideroom in the museum showing some work by Maria Hupfield, a member of the Anishinaabek Nation.[28] The work is, like, a normal amount of bad, the kinda ambiguous performance-based work you’ll find in the side galleries of most Midwestern museums. Unremarkable is the word I’d use. A word I wouldn’t use is “earthwork!” The most recent piece I could find of Hepfield’s that she describes as an earthwork is from 2005![29]

Despite this, Mr. Yearbook Committee spends an uncomfortable amount of time quipping around the space. He points to an image of the Hupfield mid-performance. “Look at how annoying these people look. Like, these are the annoying people in your art class who will try to cancel you.” What’s going on here?

If we wanted to be uncharitable, we could say that The Yearbook Committee is calling Hupfield a race traitor, framing her as the inauthentic dual to authentic Native American art that he was hoping to find in Nancy Holt. This is the explanation that makes the most sense if we view this video as a documentary, or, God forbid, an essay.

However, in form and function, Earthworks | Scorned by Muses Episode 18 is a vlog, and when we view this as a day in someone’s life, a more compelling narrative emerges. The Yearbook Committee's encounter with Electrical System is a classic transformation fetish scenario, one where a begrudging protagonist is stripped from the codes of polite society and finds himself at the precarious crossroads between man and beast. I’m sure the word “playground” set off the same alarm bells for some of you that it did for me.

I’ll give another example to prove that I’m not just being a hater. Sean Tatol’s a generally great art writer, but his recent Kritic’s Korner review of Bill Hayden’s Ding Dong[30] mirrors a lot of the issues I have with The Yearbook Committee’s Earthworks video. The review’s long and uncharacteristically descriptive, and ultimately justifies his glowing numerical rating by calling it “authentically psychedelic.”[31]

This is part of a broader trend with Tatol’s positive criticism. He’s great at writing about what he hates and what bores him, and he can talk about the canon with remarkable ease, but most of the new work he enjoys is the work he has no way of writing about. Tatol digs this hole deeper in his recent essay on Francis Picabia and Rosemarie Trockel, in which he accredits each artist's agoraphobic tendencies for their successes, a conclusion that doesn't sit right with me.[32] As an artist, I admit I’m a bit biased here. I would simply like to believe that there are presently modes of artmaking that embrace community rather than negate it, and I would especially like to believe that I am engaged in that sort of practice.

But at the same time, it did not escape me that Tatol called Megalopolis a masterpiece in the same review where he said that he “never go to the kind of movies they show at Alamo or AMC,”[33] suggesting that he may find peace if he simply left the fine arts world for the greener pastures of the modern blockbuster. As well, there is no popular arts practice more communal than the blockbuster. We may ask how many dozens of final, fleeting instances of pure creativity we can innumerate before we should call such apocalyptic framing into question.

I’m left to conclude that the sad story of contemporary art, the death of painting, the death of meaning, the flattening of low and high art, has gone to considerable lengths to exclude its field’s most engaged constituents. The artist-run spaces I discussed earlier all invariably operate at a loss. None of us have any fucking money. Before anything else, go through every single art trend of the last 30 years: web art, trash art, small painting, provisional painting, art looks the way it does right now because we do not have money. Your fave is broke as fuck and has no path plotted out towards a stable life, that is a simple truism. The people making good work right now, Bill Hayden, Paul Peng, me, are doing so at a considerable financial loss to themselves. Joshua Abelow’s the closest I’ve seen anyone come to cracking the market’s code, and even then, he seems like he’s making, like, a mid-level programmer’s salary.

We’ll return to the aesthetics of poverty later in this essay, but for now, the takeaway here is that below the art world’s highest rungs, the only people involved are fans, people with a vested interest in the canon. When I buy my friends’ work, the exchange is much closer to me burning a chunk of my paycheck on a rare Magic deck than any sort of rational financial investment in the future.

There have been a couple times in my talks with Paul Peng where he’s expressed disbelief at the specific way in which I engage with contemporary art. I had a picture of a sculpture pulled up on my phone, I think it was a sculpture by Louise Borgeois,[34] and he said he loved that I “actually liked” contemporary art. While I think this is funny and informative enough to recollect here, I also feel it is acutely important to point out the mechanics at play here, that I am a product-of more than I am a participant-in this ecosystem, and that the mechanism that produced me is commonplace.

And it’s a strategy too, like how laziness and disinterest are strategies with their own associated technologies,[35] even if (especially if) those strategies are employed without any conscious consideration. In Fans of Feminism: Re-writing Histories of Second-wave Feminism in Contemporary Art, Catherine Grant links a number of 70’s Western feminist’s cultural gains to fanatic technologies.[36] Rather than acting out of duty to country, family, or history, the fan is an intentioned outsider who reappropriates histories that have been divested from them.

What I’m suggesting here is not a retreat from academia or any other useless shit like that. We should identify fandom as the freakish, volatile sphere at the beating heart of privileged society, one that our governors have a vested interest in controlling. None of this is good, but these are the tools we have, and we ought to figure out how to use them. Otherwise, the only viable route towards producing work of immediate cultural and monetary value will be the tried and true method of dying tragically young and unproblematic.

Let’s take another look at how furry fits into this context. Furry, like everything else, would inevitably find some sort of purchase in contemporary art, first as detritus, as material for collage, then, once all the kids who got collaged into Jon Rafman videos got BFAs themselves, as enthused subjects for capital-s Serious artists. As much as Room Party is a curatorial feat, it does seem like the show, to some extent, made itself. The scene was full to bursting with artists who’ve been desperate to be in this exact group show for years, well before Room Party specifically was conceived.

The closest thing Room Party had to a press release in the gallery space was a series of four works hung in the space’s kitchenette, the oldest works in the show, four flyers for furry room parties,[37] that is, the room parties that cropped up across sci-fi conventions in the 80’s that crystallized furry as we know it today. These parties were don’t-ask-don’t-tell ligntning rods for queer culture nestled into the armpits of American commerce.[38] Sometimes people fucked and fell in love in these, but often, the bonds were more simple, watching cartoons and eating snacks, feeling safe around other people who really got it. The low oversight, hyperreal settings of the modernist business convention hotel[39] produced a militant organization of weird animist faggots. Or, is it the other way around?

I will later argue that this is not a paradox at the heart of furry, but instead that “furry” is a new name for an old thing, and that this contradiction is instead more broadly informative of the ways that culture is produced and repressed by capitalist regimes. For now, let’s identify the parallel being drawn here between the states of intentioned viewing (and commerce) prompted by both the furry convention and the gallery space. It is more than coincidence that furries have sprouted from the rubble of decaying industries, be it the tech or fine art sectors.

The most obvious allusion to these flyers in the rest of Room Party is in a pair of collages by Nate Skinner, fittingly titled room party and after dark.[40] We return to the notion we discussed with Paul Peng’s work of the no-input collage, of collage as parody of collage, of practice as parody of practice. Besides stylistic similarities in the character illustrations, these drawings were made with the exact same tools as the 80’s room party flyers: pens, sharpies, paper cutouts. If we could say any part of these arrangements is subversive to furry, collage was used in the 80’s flyers as a necessary part of the design process. In Skinner’s work, this design component becomes central to the image’s composition. Otherwise, this is pretty much just furry porn, right? Every other component of the work, the exaggerated gestures, the material, the free exchange of reproductive organs between genders, the idealized moments of intimate mundanity, is intrinsically furry. I’d argue after dark is the most bluntly pornographic wallwork in the show. Here, collage does not subvert paradigms in furry, nor is it reduced to a decorative status. Skinner has identified the ideological thread between furry and collage, both practices that arose from detritus and sexual repression.

So it’s countering some of postmodern art’s core assets while maintaining its aesthetic tendencies. New sincerity? Eh! Not really. For a work to be furry it must also be linked to a broader character performance. The fursona places a distance between the hands (paws, wings, etc.) that made the work and its audience in a way that’s extremely post-modernist. It may be a sincere expression of a feeling, but these feelings may be the imagined feelings of a cartoon wolfman, and in real life, the cartoon wolfman’s feelings are tragically out of reach. We will explore the origins and utility of this distancing process shortly, why furries would want to void their own subjectivity in the first place,[41] but the key thing here is that Skinner landed on the same sweet spot we were talking about earlier, where allusion goes beyond reference while still being a meaningful iteration on a work’s form. Skinner’s works are products of fandom in both form and content.

Skinner has simply assumed the medium of collage into their own practice. Many can only dream of an art practice that is so straightforward and yields work so rich with meaning while still being able to engage in a horizontal network of peers, free of the stressful image of an outsider. It is painting because of painting, collage because of collage, appropriation because of appropriation. It cuts the middleman by making the artwork itself the fetish object that work is produced in service of.

So the thing I like has found its footing in the contemporary art canon. Yay! However, what I hope to have illustrated here is that the exact way furry is intersecting with contemporary art is more complex than simply a shift in the field’s scope of subject matter. It goes both ways. Room Party is instead the collision of two prominent microeconomies that, since the 70’s, have craved other-sensory experiences made from our familiar tools. This juncture can hopefully provide us a vantage point to catch both branches of discourse up to something resembling the modern day.

“We read this review, I don’t know if it was Rolling Stone or some other publication, that actually said ‘They’re fascist clowns, Devo.’ And I saw ‘fascist clowns’ and, of course, we seized on that. Being the punk scientists that we were, and anger-driven, it was like, ‘Okay, fascist clowns? We’ll show you! Here’s fascist clowns!’”

Okay but, why furry specifically, right? Besides it being a thing I like? You could say the same shit I just said about furry’s intersection with gallery art about plenty of other niche communities of no-pussy-getting bloggers.

I’m gonna tell you a story, one I can tell you well because it’s been told to me several times, in person, in press releases,[42] in lectures,[43] and wherever else Tommy Bruce talks about his work.

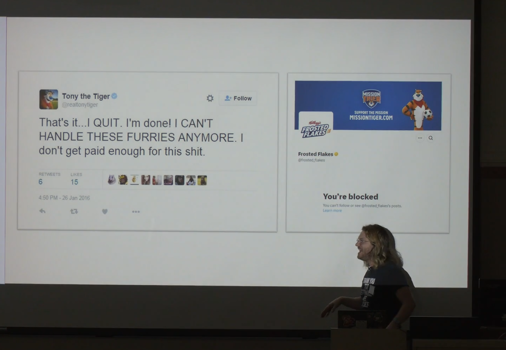

In the mid 2010’s, Kellanova, f.k.a. The Kellogg Company, created an account on X, f.k.a. Twitter, with the handle “@realtonytiger”. On this account, cereal mascot Tony the Tiger would tweet about his day as if he were a real person. For instance, a post from Valentine’s Day 2015 reads “Roses are red. Tigers are orange… Uh oh. This isn’t going to end well. #RhymeHelp”. This was accompanied by an image of a CGI Tony the Tiger model photoshopped into a stock photo of a kitchen.

The most engaged replies on all of these posts were furries who, in so many words, described how desperately they wanted to fuck Tony. Bruce would frequently appear among this horny throng. Here’s the example Vice[44] used in their reporting:

This culminated with @realtonytiger allegedly blocking not just every furry who replied to their posts, but every furry who crossed their feed in general. The account was eventually rebranded into a more generic account for the Frosted Frakes brand, apparently to “broaden the content to more brand news,”[45] but not before the intern running the account publicly crashed out about the situation.

In the wake of this incident, Bruce has made Tony the Tiger a central facet of his artistic practice. Bruce has painted his fursona into Frosted Flakes promotional material, painted still lives of appetizing bowls of Frosted Flakes, photoshopped his real fursuit, Atmus, into passionate scenes with the CGI model used by the @realtonytiger handle, fabricated several Tony the Tiger gloryholes,[46] among other things. To this day, Tony makes frequent appearances in Bruce’s art practice as a matter-of-fact muse.[47]

In 2023, Tommy Bruce and Mark Zubrovich presented a duo show of “painted works” titled Wild Desire at the Albuquerque gallery Sanitary Tortilla Factory.[48] Zubrovich, for their half, presented several wall hanging portraits of their fursona[49] in various states: big, small, muzzled, free, magically transformed, crippled, generally varied in content despite the show’s limited scope. Bruce’s work, in contrast, was varied in form, but all about Tony. The centerpiece of the show was a painted cornhole set, complete with custom bean bags. The boards in the set had either Tony or Atmus painted on them with their legs splayed over their heads, their muzzles contorted in ecstasy. Of course, the holes on each board were placed where their mouths and buttholes would be, and the bean bags were adorned with the letters of their names.

In the aforementioned lecture at University of Wisconsin Eau Claire from 2024, Bruce waxes on the initial incident on Twitter, “we won, right? Like, we found a place that advertising won’t go,” suggesting that Bruce’s fixation on Tony is simply an act of subversive appropriation. After all, a cute cartoon character hanging at full mast is the defining image of the 70’s underground comix scene that laid the groundwork for the modern furry.[50][51] Tony may simply be a useful vehicle for Bruce’s practice. Bruce is generally fixated on the ways in which a dichotomy between fiction and reality is maintained by our governing bodies, who, of course, have a vested interest in determining what counts as real and fake.[52] Bruce maps this dichotomy throughout both queer history and the history of photography.[53] What he’s saying here, broadly, is that each of these discourses is a proxy for a broader conversation on the dichotomy between man and nature, and that the central power of a government is the ability to determine who is and isn’t human.

However, Bruce’s work has an ulterior motive. Any discussion of Bruce’s work on Tony is necessarily prefaced by, at minimum, one paragraph of auxiliary information. Bruce is no lurker. He bore witness to chapters of our fandom’s history that are certainly more notable than the @realtonytiger incident.[54] If his artistic pursuits were strictly academic, Bruce would’ve surely found a muse that was more intuitive to his audience in the decade following his fling with Tony. But no, like I said, I’ve heard him orate this well-tuned monologue in just about every format you could imagine, in the sort of vigilant, insistent tone that people usually use when they’re talking about an ex or a shitty boss. Very Revenge of the Nerds.

The complicating factor here is that Bruce really does want to fuck Tony the Tiger.

This is the point where irony stops being a useful term in discussions of furry identity. When we read back the ravenously horny replies that Tony was receiving, it’s clear that everyone’s for real bricked up and simultaneously performing homosexuality for comedic effect. Everyone’s in on the joke; this character was created to put an amicable face on an evil corporation. If Tony were a real person, the engagement he received would’ve obviously been sexual harassment, but he’s not, and the mob of horny furries knew he’s not, so it isn’t.

The “place that advertising won’t go” is the realm of true self-enfacement. Brands are encouraged to expose flaws in their respective products so long as these interactions prolong engagement with a consumer. Tony can give a lot of things. He can give words of encouragement, he can be a role model, he can even sell us his sugary cereal, but so long as children are the target demographic for Frosted Flakes, Tony can not give us his body. Tony’s job is to plant a desire in you that must never be fulfilled, and his associated fetish object must only ever worsen this desire.

I know that everybody knows how advertising works, but the beat I want to emphasize here is the spiritual debt the consumer is placed in when they engage with marketing material in good faith, most often as children. Tony is beautiful and you are not allowed to fuck him.

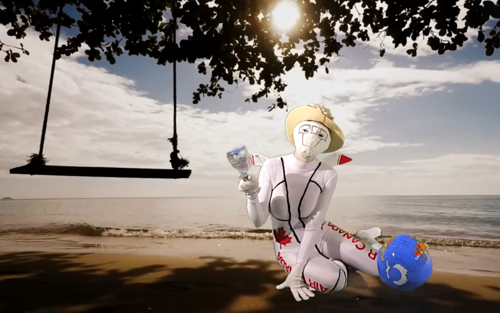

Tommy Bruce had some work up in Room Party (he, too, has pivoted to collage), but the works in the show that best reflect the relevant dynamic are the video works of Maya Ben David. In Your Goodlife Fitness gym bag[55] and Anthro Plane: Air Canada Gal,[56] Ben David attempts to assume the subjectivity of Canada’s gross domestic output through the medium of erotic cosplay.[57] Ben David is not a native to Canada, possessing both Jewish and Iranian heritage,[58] but in these works, we see some true enthusiasm at the prospect of her culture being flattened in service of her adopted nation. Air Canada Gal is cute and confident. Goodlife Fitness Gym Bag has found a deep peace in her position as a usable good.

Most vexing of all, in Anthro Plane Baseball[59] (also shown in Room Party), the two aforementioned characters play a round of pickup baseball together in a local park. Air Canada Gal is at one point coached from the sidelines by Ben David’s real life mother. It’s here that these characters exit the realm of traditional performance and enter the murky depths of the OC. It’s satire, of course, but it’s also something else.

Ben David and Bruce are both enthusiastically following orders. Their country’s dominant media told them what to love, so they fell in love, and pay tribute to these things. Irony is simply not a useful vehicle for unpacking these works beyond a surface level. Their relationships to these brands are not entirely positive, but they are complicated in the ways that human relationships are complicated. Part of a viewer’s friction comes from the ways their associated iconographies intersect with conventional discourses of commerce and oppression, but more than that, there’s a basic shocking effect of seeing these embarrassing, common, invisible modes of intimacy exposed at such an enthusiastic scale.

The simple fact is the level of desire in the world is all out of whack. It is useful for large brands to maintain a monolithic brand image. When a mascot character, or a logo, or a typeface, are centered in a brand’s image, the actions of its associated company are diluted, and it is difficult to place who is responsible for a specific decision internally. The guy at the call center gets a lot more flack for a decision than the guy at their company who actually made the decision because to an outside party, they’re both Mastercard.

So in the 80’s, Reagan gave corpo freaks the go ahead to pump American kids full of as many advertisements as they wanted,[60] and it was suddenly in the best interest of every K-12 targeted brand in the country to make whatever mascot characters they had floating around stronger, more persuasive, and more paternal. These focus-tested choices suggest some innate qualities of the child psyche that we will return to later, but for now, let’s understand that Bruce and Ben David’s work are of-media in the way that any culture is of-culture.

Let’s return to the issue of poverty. In his brief essay Decadence and Poverty, Sean Tatol defines poverty in relation to art as “a short-circuiting of decadence by means of a blunt invasion of reality that's incompatible with our usual anesthetized churn.” He defines this against decadence, a broad “state of cultural decadence, where our perception of reality has calcified into always already mediating life in unreflective and narrowly prescribed cycles, like the iron grip our phones have on our brains writ large.”[61] He is frustrated by the way our means of producing and engaging with media “extend the artifice of acting and fantasizing into our first-person experience of life.” The line between product and consumer has never been as paper thin as it is on TikTok, and it sounds corny to say because of how obviously true it is.

Tatol seems somewhat anxious to canonize his definition of poverty, conceding that many artists of considerable monetary wealth certainly fit his stated parameters. “I know that's annoying. Hopefully in the following examples a sense of what I have in mind will come through.” Poor guy! Unfortunately for him, I think this methodology is extremely useful for discussing furry’s place in contemporary art, and how it may often differ from the media-addled practices of Manhattan’s worst practicing artists. As well, we may begin to identify what makes a work uniquely furry besides the presence of sexy cartoon animals.

Decadence and Poverty concludes with a list of contemporary shows in New York that highlight certain aspects of his dichotomy. The first thing he lists is Anything but Simple: Gift Drawings and the Shaker Aesthetic, a show at the American Folk Art Museum of objects made by the titular New England fringe of extreme pacifist Christians.[62]. It’s a bunch of very plain objects (mostly wall hanging works but some furniture and tools as well) that are remarkable due to their clarity of intent. There's a wooden chest that looks like how the phrase “wooden chest” looks in your head, that sort of thing.

Tatol uses these objects to discuss folk art as a concept more broadly. “Folk art is composed by individuals who are subsumed in a collective unconscious they have little to no awareness of. That ‘poverty’ of reflection makes the work more powerful for being a far more convincing act of channeling the visionary. Only a strictly structured society that prevents modern individuality from emerging can produce such direct invocations of that structure.”

This is a fair assessment of work that is presented in a building called the American Folk Art Museum, but it does suggest a broader issue with folk art as a category. Folk art, in all its applications, aims to enumerate a list of idiots who are miraculously capable of producing good work. Folk art is a mode of criticism that appraises the author as opposed to the work, and it is commonly deployed when a work contains obvious merit despite running counter to a hegemonic art ecosystem. In effect, it quarantines the viewer from these practices. The Shakers, who exchanged their gifts in obscurity, surely have some analog in the modern world that we are unaware of, as our galleries were unaware of the Shaker’s gifts until relatively recently, but despite this, these objects place a distance between older practices and our own. Despite the quality of the displayed works it’s hard to view Anything but Simple: Gift Drawings and the Shaker Aesthetic as anything but curation as taxidermy.

There is an implied class of fakers in Tatol’s taxonomy, painters who are only interested in deviance as a means of signaling the new. But does it ultimately not make more sense that, say, Jamian Juliano-Villani is simply a boring person who’s bad at painting, that her work is not a failure to articulate a truth in our condition and is instead a true reflection of her own disinterest? Why should a perceived authenticity be a factor in determining an obviously bad work’s quality?

In his notes on his concurrent 2025 shows Installation View and Class: Weight at Miguel Abreu,[63] Flint Jamison discusses the tangential role the Shakers played in shaping the 20th century colonial project. Quoting author William D. Moore, Jamison says “the Shakers came to ‘personify’ the ‘nation’s finest qualities of piety, ingenuity, simplicity, sobriety and self-denial.’ By existing outside the mainstream, Moore argues, and yet within the trajectory of American colonial history, the Shakers ‘paradoxically…serve as both icons of Americanism and as critiques of national shortcomings.’ The paradox helped to reaffirm the persistence of America’s finest qualities, in the new light of industrial modernism.

“What bothered me,” Jamison continued, “about the turn that Moore and my friend address is not the articulation of the nation’s finest qualities, or even the arguments on behalf of American exceptionalism, but rather the argument to make the Shakers nationally constitutive, and the resemblance of those arguments to the familiar rhetoric of ‘a few bad apples,’ which spoil the police force. In the case of the Shakers, of course, we’re not talking about the bad, but rather the good, or even very good apples, which show just how pious and hard-working the nation is, at its core, and how, despite the bad apples, the core is still worth defending, regardless of what it does or has done.”

It is irrelevant whether or not the Shakers were aware of their example, but as America’s first conscientious objectors,[64] they have certainly comforted countless violent Christians that their actions are in service of an imperceptible, inaccessible inner beauty. We could consider the Shaker’s shamanic NPCs in the broader story of Protestant dominance over the New World. All of this presupposes a problematic sort of naturalized form, a way of being we have been deprived of, and are due to regain if the proper criteria are met.

This crops up again in Decadence and Poverty during Tatol’s analysis of Wang Bing’s Youth (Homecoming), a film that points an unwavering camera at China’s slave labor class. He says the film depicts “unmitigated hardship and literal poverty that's almost impossible for Americans to fathom.” Not to be a fuckin SJW but like, we also have slaves![65] We have incarcerated people working for the same pennies as any Chinese laborer, and they have similar wants and desires to all the people Bing points a camera at. What about this film first brings difference to the mind of the art critic?

I don’t intend here to needle Tatol with petty contradictions, but I would like to draw attention to the way our hegemony's rhetorical mechanisms subconsciously work in service of our borders. The presentation of any counterhegemonic work is linked to a subversion of an imagined, indescribable (fictional) natural order that we, our world’s thinking peoples, are divorced from.

This explains why Tatol values a state of befuddlement so highly. Bill Hayden’s work is so shocking to Tatol because Hayden is able to successfully evade Tatol’s intuitive system of mapping despite their similarities in life circumstances. Tatol is shocked that Hayden can speak a foreign language.

I reject a natural state. We are of-technology and we have been for our full lineage, as far back as our pre-humanity, regardless of one bubble of society’s relation to another, and all other things are of-technology as well. In furry art, furry does not signify an assumed allegiance to internet subculture or weird porn or anything else, it is simply a material reality of our current media landscape. I saturate my life with furries because those are the faggots I have found myself with, and those faggots have found each other through the relation of similar shared experience. For better or worse, these thoughts I have about cartoons are first person.

Besides working with technologies that have not yet been adequately academically defined, Tommy Bruce and Maya Ben David counter a prescriptive mode of engagement by employing a form of preemptive, parodic psychoanalysis. The neuroses of each artist are made obvious to such an extent that identifying them reads less as critique and more as appropriation. This strategy is employed by most furries working in contemporary art presently, and it will continue to be employed until furry is inevitably successfully molded into a majority-stake demographic.

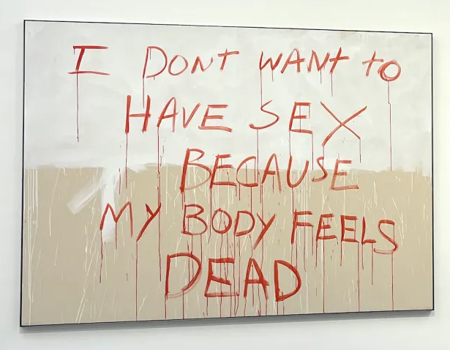

Tracey Emin is certainly a progenitor of the pre-psychoanalyzed art practice. Her art is so neurotic about her condition as a woman with a vagina that pointing this out feels obvious to the point of redundancy. We get to skip the step of finding the pussy in the O’Keeffe orchid. When we look at a scrawled text painting that reads “I DON’T WANT TO HAVE SEX BECAUSE MY BODY FEELS DEAD,”[66] the idpol that orbits the work is solved, and the viewer can suddenly view the painting beneath whatever oppressive curation it may be adorned with. We say “work bitch,” or, “me too girl,” and we really mean it, because it’s a good joke, and good jokes stay good even after they stop being funny. Comedy is the active mode of objectification.

A lot of Louise Borgeois’ best work has a similar effect. She too made work for fans of feminism. The Femme Maison simultaneously embodies and parodies each of the following half-century’s popular discourses of the body.

Outside the realm of gallery art, Beau is Afraid is another work that is so schizophrenic that any discussion that fixates on its schizophrenia would be little more than a synopsis of the events of its narrative. I haven’t seen Eddington yet but I’ve heard it’s that type beat too.

So, if idpol is generally problematic in the hands of curators as opposed to artists, we can assume, then, that the fault for this present crisis in the liberal arts may fall squarely on its curators. What has made us cast any subjectivities besides our own into the forgotten corners of the proverbial municipal Midwestern gallery?

And who is “us?” Why should the state of a particular continent’s scene (be it contemporary art or furry or whatever) hold any intrinsic relevance to the world as a whole? If our world is glut with art and information, the work of disseminating the information should be doubly placed on the curator and nobody else. I simply refuse to pity a floundering luxury market.

“And can we call it furry music if you don't slap a fursona on the cover of the album?

God damn, that's some problem, right?

God damn, well that's my problem now.”

Room Party ran from June 6th to July 20th 2025 at Bunker Projects, an art space in Pittsburgh, PA established in 2013. Bunker Projects shares a building with local hardcore venue The Mr. Roboto Project, and as of May 2024, the building is the joint property of both parties.[67] In many ways, Bunker Projects is a DIY arts success story,[68] and is generally well respected in the Pittsburgh arts community.

Bunker Projects’ programming is generally drawn from either Pittsburgh’s local pool of talent or applicants to their artist-in-residence program. Mark Zubrovich notably took up residence in Bunker in June of 2019. During their stay, they expanded on their body of work relating to the fictional homosocial rival baseball teams the Mutts and the Goodboys, which the press release at this time still referred to as “dog-people.”[72] As part of this show, Zubrovich also presented their first soft sculptures, a series of floppy pastel baseball bats. Zubrovich proceeded to not show sculptural work for the following four years until their inclusion in The Chaperone at LVL3. Here, they showed Test Paws, a pair of fursuit paws hung as to parody Bruce Nauman’s hand sculptures.[73] At this point, Zubrovich was in the process of building their second fursuit, and they had publicly come out of the closet as a furry in an article for the Bunker Review.[74]

“Furry” is clearly a label that Zubrovich felt had some stigma attached to it, and it took quite a while for them to identify what many others found an obvious part of their practice. They wrote, “I had a desire to carve out a place in that world for my own strangeness, to make it gay and cuddly and doggie and free to sniff and lick without apprehension… But IN NO WAY was that a FURRY thing! When that question came up, I could feel the closet sitting in my guts like a rock.”

The second furry to show work at Bunker Projects is Paul Peng, who presented nine drawings in his 2024 show My Subject. [75] These works are forwardly pornographic, especially in comparison to the work we discussed earlier from Peng. The drawing the show derives its title from is a close up view of one of his monster boys’ feet bathed in the flash of (presumably) his phone camera. When we compare this to the earlier works we discussed at the start of this essay, such as Versace (Reverse), we see that Peng’s primary medium is still erasure and that he is still coding aspects of his sexuality into his practice, but whereas his earlier work may suggest an imagined, metatextual piece of pornography that has been disassembled to produce his image, My Subject is single-mindedly engaged with the erotics of oblivion.

Nonstop, also shown in My Subject, is an even monochrome well of graphite, 9” x 12”, the same dimensions as every other piece in the show. If Nonstop is figurative, as it would make sense for it to be, since the rest of the show is figurative, this would be the American Evening boy’s view from the bottom of the pool. Peng has graduated from voyeur to the point-of-view character.

In both Peng and Zubrovich’s work, we are invited to watch someone tiptoe out of the closet, but at the same time, it is inaccurate to say that their current work is what they wanted to make the whole time but were too shy to release publicly. A painter’s job is to observe and document visual realities. Peng and Zubrovich, in their earlier work, were not concealing the truth of their homosexuality, they were accurately documenting the conditions of their neuroses. Their practices are distinct, but have much to do with each other.

Peng and Zubrovich did a lot of the necessary gruntwork to pave the way for Room Party.[76] They, more than most, produced the obligatory polemic work required to situate their given identity in their field. Of course, I don’t mean to suggest that these works were in any way insincere or obsolete, but it was their work that canonized a new pocket of contemporary art, and therefore, like every other group, they felt some urgency to prove that they weren’t faking it for attention, same as every other fringe (read: minority) identity. It is thanks to their efforts that Room Party did not have to have one of those godawful statements written for normie audiences explaining what furry is. They’d made the work that incidentally laid all that out already, and it had already been shown at Bunker Projects.

And again, I’m able to say all these things in confidence about this work because it’s all in the work. I do not like these works because of their subject matter. A square of wall text alone can not make me empathize with the plight of any specific masc enby. What we see in these bodies of work is an intuitive mode of faggotry in caricature, a parodic response to the condition of internal thought processes being mediated for legibility for media platforms, art practice as drag. This is a postnatural form. This is the essential condition of the fursona.

A fursona is a combination of arbitrary genetic signifiers and aspirational traits that consequently externalizes the machinations of its respective person.[77] The fursona is the clearest possible example of a pre-psychoanalyzed anti-prescriptive work of art. Each fursona contains a complex system of flagging, and to get the most out of the work, the viewer must be able to identify and intuitively respond to its encrypted messages. A fursuit teaches you how to read a fursuit.

In this way, the fursona is a useful technology for artists attempting to navigate producing work for social media platforms that have a financial incentive to override any individual artwork’s effect in service of an algorithm meant to firehose its audience with alternating positive and negative stimuli. An effectively deployed fursona will contain its own network of associations that may (briefly) override the timeline’s oppressive, fluorescent buzz.

I can’t for the life of me find where he said it, which probably means this was a conversation that happened IRL, but at one point, Bruce was talking about his Self-Care series.[78] He was saying how the image of Atmus sucking himself off was accepted a lot more enthusiastically than the image of Tommy Bruce sucking himself off even by audiences of fellow queers, and especially by audiences of fellow furries. The self-nude can signify innumerable paths of allegiance in photographic discourse. To shoot an autofellatio scene in fursuit does not bypass the questions raised by shooting an autofellatio scene, but it does answer most of them. Atmus is a (handsome, persuasive) cartoon, and cartoons tell jokes, so to access Atmus, we simply have to figure out what joke he’s telling and how he’s telling it.[79] After all, a mascot’s utility is its ability to direct a conversation surrounding a brand.

Claire Manning’s sole contribution to Room Party, titled Ratfolk Rituals,[80] draws attention to a different component of the same technology Bruce deploys in his studio practice. Whereas Bruce uses furry to mediate the distance between the work and the viewer, Manning uses furry to mediate the distance between the artist and the work.

Ratfolk Rituals’ blank front cover suggests a personal sketchbook, not meant for public consumption, commonly a vehicle for collaboration between artists in the fandom (and elsewhere).[81] Its contents moreso resemble a grimoire. Each of the volume’s fifty pages is host to a different black and white abstract painting executed directly onto its standard-issue spiral bound notebook paper. In effect, it’s a sort of show-within-a-show. The paintings vary greatly in medium. The base layer of one painting would occasionally bleed through the paper and would appear visible in the background of its dual, assisting in the production of a complex emergent symbology that makes the book truly feel like one bespoke art object.

Cool! But how does this fit into a show of furry art? Well, these paintings are a sort of collaboration, more than the normal amount that all collages are collaborations. Manning considers Ratfolk Rituals not her own work, but the work of her fursona. In this way, the paintings were produced performatively, and many of her compositional choices were made in accordance with a broader metatext, in other words, fursona as artist statement.[82]

When we talk about the burden of history that the contemporary artist faces, how we are now post-post-post-modern, how we have nullified everything there is to nullify, we are simply asking what we make work for. Work that defines an identity will not enact change. Our oppressors will not be convinced of anything by an accurate definition of the perimeter of our enclosure regardless of the degree of granular specificity these works attain. Work defining ourselves must first be for ourselves, then for those similar to us. If our automatic modes of production are at a distance from ourselves, the fursona may be a means of bridging this distance.

Room Partydid not include any of this auxiliary information about Ratfolk Rituals in its programming, which in itself is a bold curatorial statement that suggests a set of principals innate to a furry art practice that are fully divorced from its content. In other words, Ratfolk Rituals is furry art in the same way two house is a furry album.

So when I tell you that I heard Lane Linecum say offhand several times that Room Party was “a fake art show,” that should give you some idea of what that means. If that’s not enough, I guess I could start talking about the show itself, sure.

Room Party was already in production by the time My Subject wrapped.[83] The show split curatorial duties four ways, between Paul Peng, Lane Linecum (concurrent Bunker resident and partner of Paul Peng), Cass Dickenson (concurrent roommate of Patrick Totally), and Brett Hanover (and sometimes Hanover’s partner Lionel as well I think?), one of those ingroups of knowledgeable curators I was talking about. Three of the four (or five) curators were (are) Pittsburgh residents. The show’s roster, consequently, was largely comprised of friends, and friends of friends, and so on, of the core team, about sixty of them.

The show was strategically timed to overlap both with Linecum’s July 2025 residency slot at Bunker Projects and Anthrocon (July 4th weekend). Not only did the curatorial team produce a substantial block of programming that coincided with Anthrocon,[84] the team handed out pamphlets at the con describing exactly how to get from David L. Lawrence Convention Center to Bunker Projects via local bus lines.[85]

The me-and-my-friends-ass group show is a separate can of worms endemic to contemporary art, and I hope my biases towards the show are clear at this point. Room Party attached a lot of firsts to itself, and firsts are always tricky, as is evidenced simply in the list of qualifiers Room Party found it necessary to attach to its first first, “the first-ever large-scale group exhibition of contemporary and experimental furry art,” a real mawful.[86]

Room Party was generally able to back its sweeping statements up with a show that felt large, substantive, and impactful in each of its affiliated spheres of influence. The curatorial team identified the exact place and time in which they could produce their ambitious project and they filled their container more than they could’ve reasonably been expected to. The me-and-my-friends-ass group show is common in the contemporary art world for a reason. It’s way less logistically taxing than any other sort of group show and can therefore more easily accumulate a substantial scale. It’s a normal corner to cut. Room Party maintained both a big roster and a packed programming schedule exactly because most of the people involved knew each other beforehand. Plus, it is always refreshing to be able to ask a curator a question about a work and get some meaty, enriching information in return.

However, I take some issue with this approach being applied to a show that’s internally understood to be of some preemptive historical significance. Whether or not it intended to be a vertical slice of our community, that’s definitely how it came off, especially when “first”s are getting thrown around. Room Party’s engaged intimately with the minutia of furry history up until the point where it’s tasked to assemble contemporary works, where some aspects of its curation suddenly feel somewhat extraneous. It’s important for us to document our specific circuit, and this is definitely more so a nitpick about branding than an issue with the show’s content, but Room Party’s presentation draws attention to exactly who falls outside the purview of our scene in a way that feels unintentioned and uncomfortable.

To their credit, though, the team's insider trading practices are at least partially responsible for Room Party’s most substantial achievement. I think these guys actually transformed the gallery space. No bullshit. Not in the fake way you hear about whitewalls being transformed in Artforum. It was in a slight way, and it wasn’t permanent, but I watched Pittsburgh learn how to engage with Room Party in real time, and Bunker Projects felt tangibly different after the space was deinstalled. There was a reading room, and people actually used it! That’s unheard of!

About half of Room Party’s 60ish artists were represented in the reading room, whose shelves took up a full wall of real estate in the gallery.[87] It was the second thing you’d see when you came up the stairs into the space, after either the set of vintage room party posters or a lovely pastel drawing by Shori Sims. Some of them could be thoroughly leafed through in a few minutes, like my zine of brush pen drawings of one of my fursuit crushes, but some of them were long, graphic novels, high-concept site-specific volumes, hypertext novellas. If you came to the show right at the start of a standard block of gallery open hours, sat your ass down, and did nothing but skim through the reading room, you wouldn’t be able to get through most of it.

A big reading room is not unique on its own. A reading room is (theoretically) meant to enrich a show or a gallery space with auxiliary media. What’s strange is how Room Party centers these works, and how naturally the rest of the show engages with the work on the shelves. Like, Glopossum’s only contribution to Room Party was a standard issue copy of A Show of the Ropes, a comic that’s been in print since 2023,[88] and she’s listed on the flyer the same as the people who had paintings hanging on the wall. To be clear, I think this is neat, and it definitely incentivises a unique way of navigating the gallery space.

Most of Room Party’s video works were curated according to similar principals. The curators edited the individual works into a looping block of television, complete with Adult Swim style bumps.[89] Attendees could, of course, stand and watch the half-hour-and-change long program front to back, but more often, I’d see people watch some of the video works, dip out for a bit, and return to the TV when they saw something else that interested them.

The largest piece in the show, Zephyr Kim’s sculpture Theory carries all our friends on his back, was placed squarely in the middle of Bunker Project’s main viewing space. The piece is made up of several large interlocking pieces of foam. When fully assembled, nothing adheres the individual pieces together besides friction and some thread. The piece looks a lot more fragile than it actually is. I frequently saw guests tripping over Theory, knocking his paws off, and hastily pushing his dismembered pieces back together, but even when the gallery space was at full capacity, there was never any real risk of Theory being damaged in any irreparable way.

In effect, Theory was deployed as a sort of roundabout for the show. Guests who enter the space tended to navigate around his circumference clockwise, which ensured that even at high capacities, guests were spatially aware of the artwork, and maintained a slow, considered gate. It actually reminded me of the joy I felt at my first furry convention, where I, accommodated to the space, would frequently step on fursuiters’ tails, paws, and accessories. I would later find out that there was a fandom term for these positive inconveniences intrinsic to the talking animal world, that being “furgonomics,”[90] a silly and beautiful term for a silly and beautiful thing. While Kim is of course to be credited for the sculpture’s material effect, I’m especially impressed by Theory’s specific deployment in the show. He successfully acted as a formidable centerpiece, a crowd control mechanism, and an adaptation of a granular fandom concept all at the same time.

Room Party included three takehome RISO prints by different artists,[91] free, cheap works produced in the hundreds that guests were invited to take home with them. This adapted two separate furry technologies to the gallery space. A RISO print costs next to nothing to make if you’re not using a third party manufacturer, and Room Party never came close to running out of any of these prints despite its relatively high attendance. While I’ve seen some shows do clunky shit where you scan a QR code and it downloads something to your phone that you then have to go and open up in a different app,[92] Room Party’s RISOs are far and away the closest emulation I’ve felt of opening a YouTube video I got linked on Telegram. This elegant, analogue solution successfully produced a model internet within Room Party.

Additionally, we can see these RISOs as another sort of centralized auxiliary media, meant to be carried around the gallery space and read at the attendee’s leisure. The takehomes are a means of extending the heightened space of the gallery into an audience’s home in an identical manner to a convention’s dealer’s den. At their own pace, Room Party invited viewers into ambient modes of engaged relaxation. The curators assured that there were ways to comfortably engage with the show from the vantage of its leisure areas.

And the bed! I haven’t even mentioned the bed yet. There was normal style seating in Room Party, chairs and tables or whatever, but the place most people ended up sitting to read its many printouts and zines and whatnot was a queen sized bed that was set up in the gallery space. The bed itself was not listed as an artwork (I sadly couldn’t drag Tracey Emin into this essay a second time), but it was adorned with betsheets designed by Wolf Kin and a dakimakura designed by Cate Wurtz. If I really wanted to stretch it, which I do, I could say that sprawled across that bed, reading the text-based work in the show at my leisure, aware of (but not at all distracted by) the real warmth created by its coverings, I was engaged in the performative, disorienting mode of ease commonly felt by the fursuiter as they occupy its padded flesh. I was instructed to rest, so I did. The Room Party bed was a gathering place. I saw it host anywhere between one and ten people at a given time, strangers, lovers, all that.

A photo of Wurtz’s dakimakura appeared in a collage, also by Wurtz, hung next to the bed. Its artifice informs reality and vice versa.

To identify the specific way that Room Party transformed Bunker Projects, I felt the same way seeing pictures of deinstall that I generally feel when I’m driving past the David L. Lawrence Convention Center out of season. Room Party did not pierce a membrane that separated furry from the world of contemporary art. Instead, Room Party expanded the furry convention into the gallery space, in the same way that Puppies Puppies’ Condom Filled with Spaghetti is not a reference to a meme, it simply is an iteration of a meme.

More so than any tokenized achievement in the history of marginalized art, Room Party was the world’s longest furry convention, and it was the restricted, regular hours and localized consideration of the regional art gallery that allowed it to successfully translate the furry convention into its prolonged format. People traveled hundreds of miles to see Room Party. Locals came back to Room Party several times, many time more than the normal amount people visit art shows that they like a lot.

For as long as Room Party was open, it was one of those third spaces queers always talk about, the sorta place to go to engage with a community that’s entirely your own for its own sake. For you believers in a forthcoming queer utopia, first of all, keep fighting the good fight, second, pay attention to Room Party. Note the ways it paced out its programming. See how it mobilized its area’s NEETs. This isn’t a hypothetical instruction. I've heard word that several such millitant faggots have already seen it fit to harass their local mid-low rung galleries for group show placements as a direct consequence of Room Party’s success.[93]

That’s not my bag, though. I’m in a weird place. To me, each of Room Party’s successes largely serve to highlight the sorry state of affairs we’ve grown into, and I can’t imagine Room Party in itself leading to any sort of radical change, as art is substantive largely in proportion to its uselessness.

“In putting honey on my head I am clearly doing something that has to do with thinking.”

Room Party was the occasion of the first artist talk I’ve ever been invited to, on July 6th, the afternoon of the ass-end of Anthrocon. I was placed on a panel of indie publishers each significantly more experienced in the field than myself, including Shiny Skunk, one of my co-curators on Yiff! Magazine. I didn’t want to embarrass myself at the talk, and I don’t think I did, so I’m thankful for that, but I couldn’t shake the feeling that I was acting as somewhat of a wet blanket on the show’s unbridled optimism.

Specifically, I brought up how Yiff! was printed through a third party printer, Mixam, whose US manufacturing unit is based in Chicago. I got some substantive pushback from the panel of artists when I brought up how our furry forefathers surely would’ve used mass-market printing units like Mixam to spare their budget and workload if these tools were readily available to them (Mixam specifically was founded in 2003, and their web-order service would not launch for several years after the fact).[94] I did not feel like this panel was feeding me questions specifically in service of affirming a DIY ethos, but I did ultimately exit the panel feeling like I didn’t give the answer I was supposed to.

Because DIY sucks. It sucks to do DIY. The work I produce fits into a DIY ethos simply because America does not have a niche place for my (our) work besides hands-and-knees-groveling art shows that nobody makes any fucking money on. I wish I was able to settle on something more positive, lean into the “first”s that Room Party is so proud of, but on land that is hostile to our work, that only aims to affirm instead of upset, we may have done nothing more than construct our own show of Entartete Kunst. This is why I advise against such sentimental modes. When we historicize our present moment, we transform present achievement into future defeat.

Is this not the goal of our liberal apparatus? To enumerate the granular details of our agonies? When we identify that our innate animist qualities have been subsumed in service of our oppressors, should we not rage? The fetishization of DIY, the ideation that it may be the only way to produce art in a natural way, and that an artwork’s quality may be determined by the metric of its sincerity, reiterates the most regressive libertarian ideologies in service of an extinguishing mode of self-repression.

When I look at American Evening, when I study Peng’s gleeful suicide, I wonder what will become of furry once it is generally understood the substantive minority group that it is.

In December 2014, the largest chemical weapons attack of America’s 21st century was perpetrated against the attendees of Midwest Fur Fest in Rosemont, Illinois. Local news reporters laughed at the case because it happened to faggots instead of normal style people. Rosemont Police were uncooperative in relation to the case, and no suspect has ever been named in relation to the attack.[95]

In 2024, Dragoneer, the owner of Furaffinity, died because he was restricted from accessing lifesaving medical attention due to financial strains brought on by the American healthcare system.[96] We memorialized him, but we ultimately didn’t do anything. We didn’t protest. We took his death for granted, as we have so many times before.

Fandom is a relegated domain. Fandom is where our liberal apparatus pushes groups that run counter to its hegemony, not even threaten it, run against it in any meaningful way. If Room Party is to be the “beginning” of anything, I can hope it can internally elaborate our exact mechanisms in the hopes they may be replicated in the future.

So to DIY is to self extinguish, and to embrace DIY uncritically is to celebrate our own nullification. We may produce valuable art while we are extinguished. These means of making are innate to us, and the work may persist, but we will still be quenched in the same dark swimming pool. It is time to think again of us, the animals that make our things.

And as for “conteporary art,” y’all need to start killing people. Stop worrying about the arts being defunded. It’s happened. There is nothing left to defund. The fact that we persist is not a testament to the power of art, it is a symptom of a tragedy on a broad scale. Aim for the judges and the bankers, those are the ones who really hurt.