There is a self evident connection between ghosts and doctored photography. The first images the term “ghost” evokes are those of photographic hoaxes, Raynham Hall and all that. Modern ghost hunting television programs bear these traditions, the half truth that titillates the notion of an undiscovered world. These images are intrinsically fabricated.

I know that this image is fake, though I can not tell you specifically why. My eyes put a lot of stake in images, and the process of looking at them is a very intensive one for me. I have become familiar with millions of ways by which an image can be inaccurate to the subject it depicts. I am reinforced when I can understand why something in an image is fundamentally incorrect, and reappraise my relationship with the image accordingly. I know about double exposures and reused film stock and the general weird shit that can happen with old cameras. With this knowledge, this image does not frighten me. I speak with hindsight, though. The original audience of this image would likely not be as keen as I am to these things. They felt as much as I do that photographs depict images of real things, but they lack the information that I have that helps me rationalize the errors in this depiction. The “mistakes” in this photograph are separate to me in a way they were not as much to those uninitiated to the technology at hand.

Or maybe they weren’t frightened at all, and this is simply a more recent digital edit of an older family photograph. That prospect frightens me even less. I have spent many hours operating transparency layers in Paint.net myself. I have taken the steps necessary to fabricate a ghost photograph in this manner. Maybe I am the original intended audience of this scare, and I am simply too sexy and intelligent to give it much thought.

That’s how I feel at least. I can’t ask these guys if they thought there was a ghost there for real. Maybe it’s like the War of the Worlds radio broadcast, where people thinking it was real was something that was just kinda invented over time. Maybe these images were party gags or tech demos and I’m sitting on the whoopee cushion.

The people in this photograph also thought that photography was as advanced as it would ever get, besides a vague gesture towards future tweakings of the same fixed components. The transition from early photographic techniques to modern technology is overwhelming if viewed from a distance, of pinholes in boxes to 4k home video cameras, but each step between these points was slim. Whatever progressions in the field I’ve experienced in my life have come slowly. The advances pass through me and leave me unchanged by their voyage. It feels like nothing has changed at all, though that’s obviously untrue.

You can technically make any image you wish. You won’t be doing that, though. Most images still elude us despite our newest ultimate set of infinitely plausible means of capturing and tweaking the appearance of objects. You can make semi-accurate deep fakes with relative ease now, but if you spent a lifetime on one previously, you could surely create similar ones with MS Paint and Movie Maker, just as you could create them with ink dots on paper before. The deep fakes we have now also do look pretty ass. I at least can still identify fake images from real ones in most cases, like how you can tell what is and isn’t CGI in a movie, it’s a gut feeling. Any image can be made, but a lot of them won’t be.

I may just be stupid then. I can write out most of these things as a series of reasonable causal relationships, but I conclude distrusting my ability to classify images as real or fake. If there is any clear difference between me and the hypothetical haunted plantation family posing for a local newspaper, it would be that I have seen many more images than them. I may be under an inflated impression of my ability to distinguish reality from fakery, just as they were, but I know many more ways by which a photo can be fake, and generally have a better idea as to where they come from. Most of what I do is look at images. It’s incredibly easy for me to know when an image is doctored. I know when I see a filter on a TikTok, and etc. If anything, I have an inverted problem, where I am not as easily able to identify an accurate depiction of an object.

It takes a long time when I look at a picture of a real dead body for me to stop seeing special effects. I have enumerated such a large catalogue of fake gore in my head, against such a minute catalogue of the real thing, that there’s few ways to make something like that really look real. It often looks fake. Whenever I go for drives, I can’t help but view the process from the perspective of a cinematographer. I take scenic routes that do nothing but impact the things I see on that passage. I occasionally go so far as to take my camera with me, and photograph the things I see along the way that strike me. I’ve so often ended up with my flashers on, pressing the delicate shoulders of the backroads of these places, fictionalizing whatever images strike my fancy.

I don’t trust pictures unless they’re taken by people I know. Everything else looks as real as everything else.

There are ghosts roaming the digital realm. A photograph of a person can represent that person, and a photograph of a dead body can represent that body as well. However, the person and the dead body can not be blended in real life, though they can in the realm of photographs. Who is to say what that intermediate photograph represents except for a ghost? This is the closest we can come to a tangible depiction of a ghost, a spectre not living or dead, that persists in one moment.

It is not a matter of whether or not any of the hundreds of hoaxed ghost photos I have witnessed are “real” in the sense that they captured an image of a spectre, it’s that I literally would not be able to tell if they did. The only thing preventing all of these photos from being real is my own judgement. The space between these two things is such a horrible burden to bear.

Who is to say, even, that ghosts are not real because we are not able to photograph them? If all the scholars of the world descend at once into the world of images, discerning what is fake or real within every piece of media ever recorded, in the past and present, building a book of the images in real time, what is that to do with ghosts? Where in any historic definition does a ghost not exist until it appears on an EVP machine? What business is it to us to decide what ghosts do and don’t do? What of a piece of information deliberately unknowable?

Thus derives the need for media without origin: found footage, petittube, for those less tech savvy, the “weird side” of YouTube. For horror storytelling to be inexplicable, it is necessary to simultaneously author the frame of the text alongside the text itself. I will refuse to believe any images of ghosts shown to me, but I can believe that there are unknowable forces creating the images themselves far away from me under the guidance of motives I do not understand. When there is a distance between me and the piece of media I am viewing, when I am not able to assess its intent or formal qualities by any metrics of media I am familiar with, ghosts begin to appear. The photograph of the ghost simultaneously creates a landscape of equitable truth between all images and shifts the subject of suspicion onto the photographer themself. I do not know why I am shown most of the images that are shown to me. In that space, the corpse merges with the image of the living person.

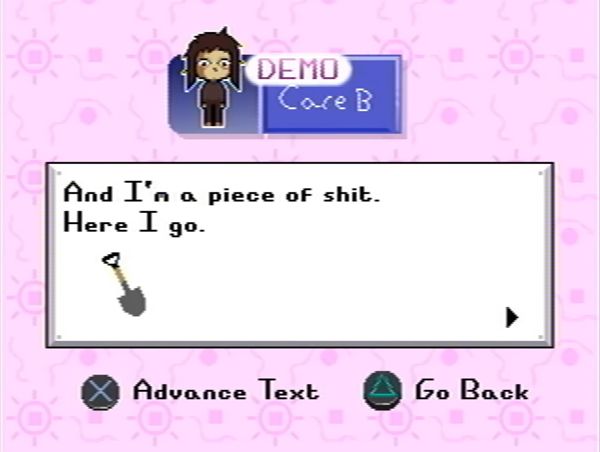

This begs the question: is Petscop a haunted video game creepypasta?

“This game is trying very hard to make it seem like, um, like there's an entity in it. Like, uh, a ghost, or an AI, trying to communicate with me. It's interesting. But you know, the way you know that there's a ghost in a game trying to communicate with you, is if it comes out. If it stops being distant, and it comes out, and you can have a, you know, a real-time back and forth with it. Um. And it stops being so one-way.Like I, I leave my PlayStation, and it comes, comes out and, uh, does this whole pre-recorded thing. Uh. And, well, the closest thing that's happened to that, is last video, you know, it actually answers my questions. But, you know, it only responded to two of my questions, and the first one, the first question I asked, it didn't even answer that question. So, uh, no obvious interactivity happening. You know, and, it answered the second question, but that could have been a coincidence. Um, yeah. So, uh, not entirely convincing yet. But, you know, looking forward to what I might see next.”

The manner in which Paul broaches the subject of Petscop possibly being haunted is comical in its understatement. After five videos of unusual occurrences in the strange video game he finds in his house, dancing around the notion of Petscop’s existence in a broader context of online horror storytelling, Paul states the obvious: Petscop looks like what creepypastas look like, and is doing ghosty shit. It would be the perfect point for a different project to jump the shark, to utilize the slow burn of the first few uploads as a groundwork for a campy PS1 horror romp. Instead, this passage lays dormant. It casts an odd shadow on the events that proceed for the next several uploads. The questions it poses are suspended in place. The AI in the game does seem a bit too advanced. The puzzles do seem obtuse to the point that only Paul (or whoever else is playing) can solve them. This shadow never fully goes away, nor to “introduce” itself in any lasting capacity.

Many locations in Petscop are based on locations in Paul’s real life, such. This does not mean that Petscop is haunted, but it does mean that who/whatever created the game is aware of personal details relating to Paul’s life. Paul mentions even seeing the best lead as to who created the game, Rainer, at a birthday party as a kid. It is unlikely that Rainer would undertake a project like the creation of Petscop specifically for the consumption of a person as remote to him as Paul. A lot can be derived from Paul and Rainer being in the same class, however.

Paul speaks of several places in the game in a familiar tone, as if he and the people he’s making the videos for would understand the locations he and the game allude to without further extrapolation. Whatever person or people Paul is making the videos for, be them siblings, school friends, or whoever else, know what these places looked like when Paul was in early schooling. I work from the assumption that the person Paul is making these videos for is at least as close to Paul as Paul is to Rainer.

If we accept that, this seems cut and dry. Rainer’s some sort of stalker who created a game about whoever he had beef with from when he was a kid and all of the people involved have to combine their efforts to crack the game’s riddles. That’s not what Petscop is, though. Nobody comes together.

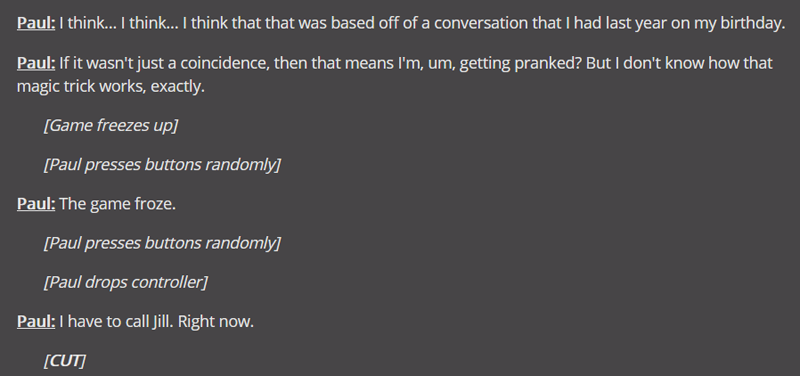

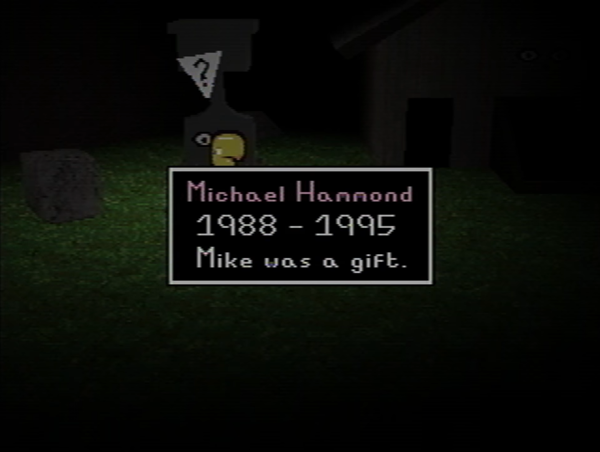

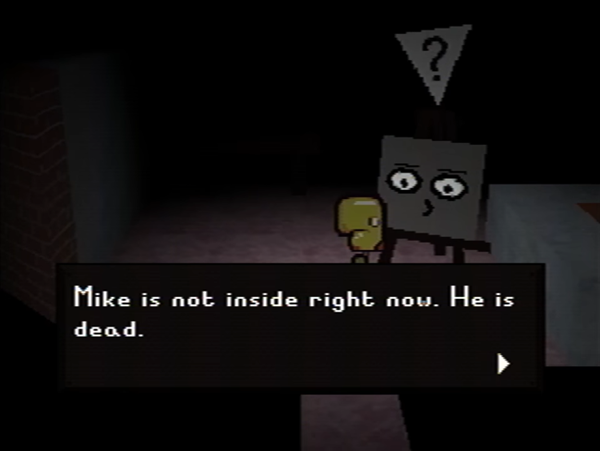

There are two instances I can discern in which the game introduces itself to Paul directly. In Petscop 14, the game displays dialogue that Paul claims was a replication of a conversation he had at his birthday party in 2018. Petscop has been in Paul’s possession since at least 2017, and Petscop 14 was uploaded in mid 2019.

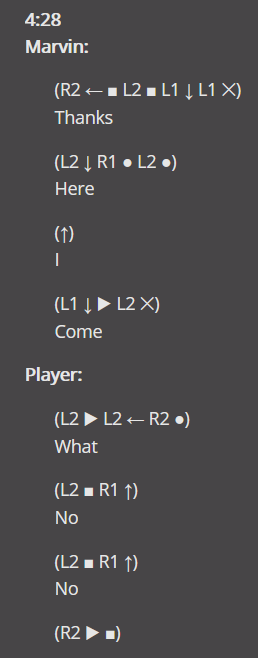

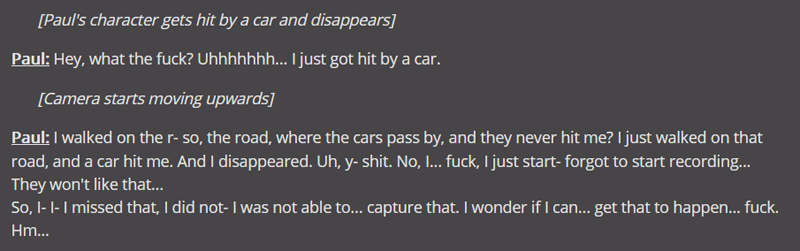

The other instance comes partway through Petscop 23. Marvin enters the room Paul is in and addresses him by name. He asks Paul to pick what room he is in from a number of pre-arranged layouts. Paul correctly identifies one of the layouts as the same one shown in the alert sequence in Petscop 16.

Paul wiggles around the option, his only means of selecting the given arrangement. Against logic, Marvin addresses the gesture.

Paul leaves one of these words incomplete. It’s impossible to tell how long this word hangs in the air due to a cut in the video. However long it did sit out in the open, it was long enough to trigger the only “Not In Table” notification seen in the series.

These two instances mirror each other. The game introduces itself to Paul, and Paul steps away from the game. The player character remains in one place for an indeterminate period of time due to a cut in the footage. After a prolonged period of inactivity, the player character moves again.

The main difference between these clips, besides their context within their respective parts of the story, is that Petscop 14 has audio commentary from Paul and Petscop 23 doesn’t. We know exactly what Paul does when the player character is inactive in Petscop 14. We hear him drop his controller. We hear him stand still and contemplate. He is silent but present, as he is throughout a lot of Petscop up until this point. Paul doesn’t say anything during these prolonged pauses in either 14 or 23. However, in Petscop 14, we know where Paul is relative to the game. He is nearby, breathing, thinking of how to approach the information he has been given. In Petscop 23, we don’t know if he is or isn’t doing anything. This is uncharted territory, anything could be happening. Both of these clips are silent besides additional ambiance from the game. In two parallel instances, the same amount of audio input yields a drastically level of output. In the same absence of audio, with different levels of input, Paul is in one instance present and in another not present.

Paul is alive in Petscop 14 during that moment of silence. I can’t say anything for sure about Paul in Petscop 23. The key thing is that due to that lack of input, every option is exactly as true as every other, with concession for the context of the broader tone of the artistic work and the will of the game in universe. We’re left with his half language. In those moments where nothing moves in Petscop 23, a ghost is created through Paul’s absence.

After the initial introduction of a spectre in Petscop 14, only Petscop 22 contains audio commentary from Paul. Even then, the commentary in 22 is voyeuristic and distant. Paul’s on the phone, presumably with someone he’s making the videos for. He is talking about experiences and theories relating to Petscop while playing Petscop, half paying attention. He only becomes engaged in the game when an anomalous event occurs.

The only other instance of audio commentary past Petscop 14 comes when Paul is unaware he is recording gameplay footage. As the clip ends, a figure he’s seen several times before emerges. Paul speaks to it directly. He introduces himself to the game, on the defensive, a prospect unthinkable earlier in the series.

“Hey. You there? Hello, you there? Hello?”

Where’s Paul?

In most horror narratives, the audience is brought closer to the horror in question as the story goes on. Tension builds either as a threatening force or forces are made more obvious, given more time to linger in the audience’s mind, are complicated by extenuating circumstances, etc. A character or cast of characters are usually acted on by whatever force is at play, and the audience’s reactions coincide with the event of these characters being acted upon (in the case of more abstract horror storytelling, the audience themself is the one acted upon). It is art that actively requires the participation of its audience to be classified as it is, like comedy or tragedy.

What makes Petscop unique among other horror narratives, besides its play with format, is that instead of action onto the avatar and the audience unifying more overtime, the things that happen to Paul move further away from the audience. Paul retreats into the editing room as his gameplay becomes obsessive. Pieces of iconography, the windmill, the school, the birthday cake, link themself to his life more specifically over time. As these connections solidify, it is increasingly in Paul’s best interest to remove himself from the equation. Every piece of information he shows, or censors, is a clue to his real location.

Petscop acts on Paul in a manner that increases his paranoia and obsession. Consequently, Paul, the narrator, grows less reliable or even coherent as the series progresses. He codes the work in a manner as . His understanding of Petscop’s iconography is in direct conflict with the understanding of the audience. Petscop is one half of a conversation. As we grow distant, as these things introduce themselves in increments, as the AI becomes advanced, then likely the result of input mapping, then interactive beyond reason, it feels like nothing at all.

The closer Paul gets to a ghost, the more transparent the ghost becomes. It is not the duty of the ghosts in Petscop to make themselves obvious to us, only to Paul.

It feels as though Petscop would exist with or without me viewing it. It certainly exists in an ambiguous form despite the best efforts of prominent gazes who wish for all narratives to conspire into a package immediately available to them, those concerned with the action of photographing the ghost.

Another ghost forms in Petscop in the spaces between uploads. The uploads that comprise the bulk of Petscop’s content were recorded and compiled around the time each respective upload was released (recall the calendars in Petscop 14). We can assume, then, that Paul began to play Petscop a bit before March of 2017 and reached Petscop’s “ending” around September of 2019. During this two and a half year period, Paul, and whoever else, play Petscop enough to find the game’s debug menu seemingly through trial and error. The details of every chart, date, coded message, and so on, however incoherent or stunning they are to us, are obvious to the intended audience of Petscop (recall Petscop 23, how Paul was able to immediately recollect the position of the room displayed in Petscop 16).

This is to say that Paul has played a lot of Petscop. Furthermore, the “room impulse” section of the debug menu contains cycles of input maps that can be alternated through and taken control of at will. In Petscop 17, Paul unlocks information critical to his investigation by negotiating these input maps within a menu already buried beneath a cheat code fully inaccessible to the viewing audience of the series. We’re very far away from Paul in this moment.

Within Petscop are the memories of many playthroughs of Petscop. It is a game with an expansive history that continually writes itself through investigation into its mechanisms. The debug menu’s recordings include information that is necessary for Paul to proceed with his investigation. Simultaneously, Petscop incorporates Paul’s lived experiences into its body of work. Paul’s experiences are reinvented as a subject of observation. Beyond its surface layer is an expansive sub basement of forbidden knowledge that grows as it is prodded in increasing degrees of codification. In this way, the architecture of the game world mirrors the way in which the game communicates knowledge.

Whatever knowledge Petscop contains is immediately made inaccessible to a vast majority of viewers by the circumstance necessary for their description. Those to which this knowledge is accessible only exist within the universe’s fiction. It’s not frustrating, though, at least not for me. It’s enough for me to be near Paul as he negotiates his past experiences. For as far as I can feel from him at points, it is still a let’s play. When Paul finds a new face, I say “oh cool that’s another combination he can use in the face codec.”

Usually, he obliges.

Paul’s a smart protagonist even if he’s not always working towards my goals. As his memory performs itself in front of himself in Petscop 14, I understand his distress, even if I personally am more distressed by the imagery of the uploads, the dead kids and dark pathways, these facets of Petscop’s universe that seem very natural to Paul. Though our goals are in conflict, Paul never antagonizes me.

I hope I have not made the case for Petscop as a piece of abstract art. Even as the series expands its web of coded messages, fragments of text continue to carry the weight of previous narrative elements. The narrative elements near the very end of the series were especially compelling, fitting as Petscop only seemed to actively antagonize the player in these passages. Seeing symbols recur and being in the presence of someone else for so long was really comforting. It’s not abstract, though, it’s just not meant for us to see.