This topic is such that I will, at points, be making assertions about the intentions behind artists’ work, some of who are artists of color, or are otherwise not American. I am also an artist, and I want my critical writing to be constructive! If you catch any info in here that you feel is flat out wrong, feel free to reach out to me, I’d love to talk it through.

I went to a show the other day. It had only just opened, in a small art space in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania called Romance, but there’s a good chance you’ve seen it before: a handful of mid-sized paintings reproducing photographed images in precious detail, plus a few sculptural interventions to tie everything together. This one’s by Tasneem Sarkez, and it’s titled Just For You. The press release says that most of these pictures were sourced from “the corners of the internet and corner delis, smoke shops, beauty salons, and street vendors in New York,” though Sarkez herself is native to Portland, Oregon.[1]

There is certainly some sort of lived perspective present in her paintings, in the way that you can learn a lot about someone by going through their Twitter likes, and Sarkez is clearly pretty good at painting.[2] The best bits of painting in the show are the moments where Sarkez emphasizes the counterintuitive moments of composition that emerge from careless digital photography. I especially like the overwhelming flash in Peace Plan and the ways the toxic green light warps through the hookah in Hi Jolly.

But as usual with these sorts of paintings, I lose my footing in the cavernous gap between the press release and the work on display. I truly can not tell you what Hi Jolly the historical figure, an early Arabic accessory to the American colonial project, has to do with a hookah that looks like a gun. The painting and its title both vaguely gesture towards histories of violence and assimilation, but I truly don’t know what work I’m supposed to be doing to synthesize these parallel threads into something meaningful. I’d definitely have more to do here if this were a photograph, one with a provenance could be sourced to a specific avenue. This image may be from a defunct blog or a house party (or more likely an aesthetic blog), but this painterly green film, and moreso Sarkez’s insistence on authoring the image themself, yanks the original photograph away from the world, making it the worst sort of photograph, one with no tangible offscreen space.

This issue is worsened by the prerequisite found object sculptures being obviously the best works in the show. Beautiful Sexy Angels Await You in Heaven is an LED sign that scrolls through its own name. It is bodega ephemera. Removed from its original context, it accrues meaning through its ambiguity, meaning that is explicitly tied to the American Arabic diaspora. It succeeds in exactly the ways the paintings in the show fail.

I’d like to draw attention to partial documentation of an art book by Sarkezs, titled Ayonha, available on her website.[3] This work utilizes a similar set of subject matter to Just For You, though Ayonha is a considerably stronger body of work. The images in Ayonha are collaged, reproduced, and juxtaposed through a variety of mediums. It’s less stiff in the shoulders. it increments on the imagery being worked, the ways it obscures its content draw me closer to the work (offscreen space is certainly present here). I have an avenue to access Ayonha in a way Just For You doesn’t provide me. I bring this up to assure that I do not have any sort of issue with the subject matter Sarkez focuses on, or even an innate issue with the techniques she deploys.

Now, while I personally will generally prefer painting done from life, imagination, or some sort of non-aesthetic process, I should note that there is a big difference between using a preexisting photograph as a reference image for a piece and the aimless mode of photo-painting I’m talking about here. To copy a photograph in paint, to aim to imitate photographic qualities, is to have each aspect of your works’ composition, palette, surface texture, and emotional affect predetermined for you. No painting techniques are intrinsically good or bad, but this specific mode of imagemaking forfeits so much of an artist’s input in their painting that they really ought to have a decent reason to make it a central facet of their practice. I can’t imagine it’s particularly liberating to one’s practice to have to paint the same sort of shit in the same labor intensive way ad nauseum forever.

The best working photo-painters are conceptual artists in equal or greater measure. Hamishi Farah is easily the best working painter of photographs, and their work is essentially about the labor involved in (re)producing a photographic image. For instance, we can look at their Black Painting series.[4] A key part of the series’ intimidating effect is that they were each created by hand, that their variances in scale, which could be executed effortlessly in a printed format, were each painstakingly considered. Moreover, they are clearly arranged in consideration to the gallery space, such that the viewing audience would be the white pieces on the chess board. The work manages a blunt gesture while concealing some of itself, and the individual works in the show have considerable merit besides their application as prop.

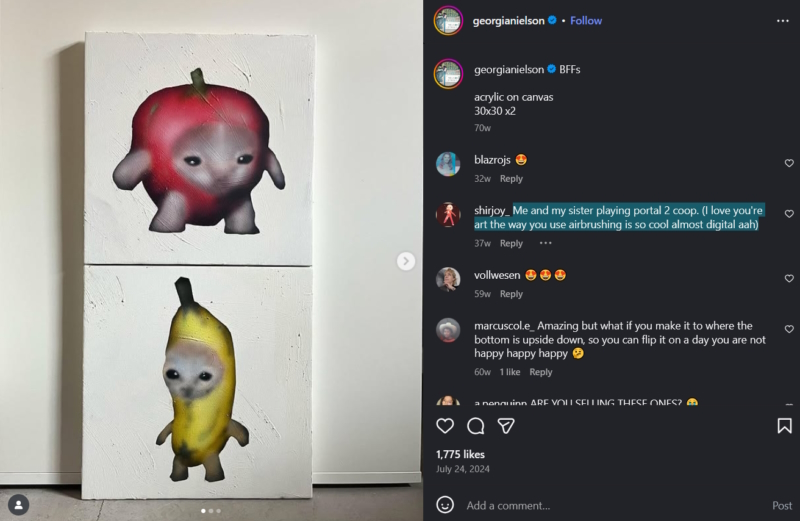

Edie Duffy’s work is also relevant to this conversation, though her work is overall less interesting than Farah’s. Duffy paints photos of items listed for sale on eBay (or Craigslist or some other website like that).[5] Her painting is rigorous and technically impressive. Her palette captures the dull greys and sharp shadows endemic to consumer grade digital photography, but she is not interested in recreating the digital artifacting of her source images. She instead paints as though she, too, were inside the camera’s viewfinder. In this way, her paintings are only as valuable as they are able to accurately clarify the data missing from the images she sources. So, her work, though much more laborious, is identical to the labor performed by the person writing the descriptions of the original eBay listings. The more accurately each item is defined, the more value the item has on the market. It’s a very funny position for her to place herself in.

That being said, Duffy seems to have locked into this style fairly recently, and she’s fairly young. If she continues to do this for the rest of her life, I think having, like, a thousand of these in a room together would be pretty fantastic. Otherwise, I’m unsure what this style will yield beyond what we have here already.

I ignored it at first, but the more shows I saw that shared the same shallow pool of vaguely taboo subject matter,[6] careless brushwork,[7] and weak conceptual backing,[8] pop up in all sorts of venues, old institutions, big institutions, seemingly without a geographic hotspot or web manifesto pumping blood through its veins, it really started to confuse me.

When an artist comes up on my timeline, and their gallery is full of paintings of the Rainbow Dash cum jar, or Jeff the Killer or whatever,[9] my only thought is that they don’t know what to paint. Even when it seems like the artist themself made the meme they’re using as reference material, I’m almost left wondering why they didn’t just show me the weird meme they made, especially when the work is primarily being showcased on a platform like Instagram that’s catered towards sharing memes with each other.

Again, I’m not categorically opposed to any given trendy Instagram style (Gao Hang is obviously the best of the airbrush guys), nor any specific subject matter, but goddamn. Every Grégory Sugnaux looks the same as every Julia De Ruiter looks the same as every Tasneem Sarkez. Like Edie Duffy, their work is only as valuable as they are successful scribes, and their work only depreciates in value with each imperfection.

I mentioned in my writeup about Room Party[10] that iconography appreciates in value as it is replicated, and that is still true here, but the key thing is that none of these artists made the iconography they are replicating. Julia De Ruiter’s painting of the Rainbow Dash cum jar further canonizes the Rainbow Dash cum jar as an event in the broader internet vernacular, but the painting itself is unambitious, and only depreciates in value the more it deviates from its source material. Maybe that’s why this work is so often housed on Instagram first, it’s a lot harder to notice shoddy painting on a screen.

I’m not the first person to problematize this trend. Actually, I’m pretty late to the party on this. I put off writing about this for a while specifically because this shit’s so widespread that it didn’t feel helpful to shout down at it without having something to propose in its place (so, look forward to that). Despite this, there’s still no consensus on what this blip in the trend radar was/is, what it’s called, what it signifies, anything really. It’s too biographic to be pop art, not painterly enough to be an imagist movement, too painterly to be theft, and there’s no social component to it, so it’s operating at a level below a Banksy-type institutionalized street artist.

Later in that same writeup about Room Party, I alluded to a group show that specifically cited Room Party in its internal pitch documents. That show, titled The Self Imagined, opened July 14th of this year in Carol Scholsberg Alumni Gallery at Montserrat College of Art in Beverly, Massachusetts.[11] Its subtitle reads, “gen z avant-garde is here,” a militant slogan to be sure. The show was curated by Piero Roque, who, after the close of the show, co-launched Gallery Dog,[12] an online curatorial platform that shares its core mission statement with The Self Imagined.

I’m not going to go into an in-depth critique of this show (besides the curator still being a student, I was not able to see the show in person, and documentation online is sparse), but since this is the only boots-on-the-ground zoomer I’ve seen attempt to frame this current wave of picture paintings as part of a broader artistic movement, I feel like this show is worth bringing up.

The most interesting aspect of Roque’s proposal is their simultaneous antagonism towards identity politics in art (namely, cultural institutions that expect minority artists to exclusively produce work that relates to their cultural traumas) and their paradoxically single minded focus on a work’s subject matter. The work featured in The Self Imagined, as well as what gets spotlighted on Gallery Dog, varies greatly in every manner besides them all being paintings of internet-related things, and even that’s a stretch sometimes (Marilou Bal’s gimmick reads as more as a 2000’s digicam throwback than a zoomer brainrot thing).

In Roque’s recently digitized zine Introduction to Gen Z Avant Garde, after enumerating a series of artists they feel fit the category they’re defining, they write “the subject matter we have long been familiar with, these artists are just a few who are giving it a new context. They couldn’t possibly cover the entire [internet’s] legacy alone. An exciting opportunity arises to talk about the plethora of unaddressed internet topics, and you have a duty as an artist to elevate unheard voices! Make your thesis work [about] Homestuck ships, your old memepage, anything. The floodgates are open.”[13] I encourage this sort of enthusiasm in all its forms, but, is this not just another id-pol based art practice? Once the furry femcel body has been accepted into institutional discourse, what will become of this purported movement? I am fully in support of curatorial projects that take otherwise disposable online artwork seriously, but all of the works showcased on Gallery Dog are already keen on drawing attention to themselves. Theyr'e not memes, they're paintings of memes, which is a slight but important distinction.

I’ve seen Roque posting pretty often on their story about their disillusionment with art, not just with the cultural industry that surrounds it but with their personal arts practice as well. Piero, please keep reading! I have a proposal that may pique your interest! I have to talk about some other stuff first, though.

Like, I guess I should talk about Richter if I’m talking about all this other stuff. I GUESS. I’ll say that Richter’s practice made a lot more sense back when the world had less pictures in it. It’s not just that he typically worked at a much larger scale than most contemporary photo-painting artists (something something recession indicator), it’s that pictures served a fundamentally different purpose in the 1960’s than they do today, and they look a lot different too. This is also why most of his absolute cornball work came after the advent of the 24-hour news cycle. His 9/11 painting[14] is the most blatant example of this, but the Baader Meinhof series is also extremely embarrassing.[15]

As well, the labor required to produce an artwork is always, always contained in the work itself. It is as much a part of the work as (and is often the cause of) all of its visual qualities. Matthias Groebel’s early printer paintings are fuckin’ sick entirely because of the janky technology he used to produce them. Though he still often utilizes printers and plotters, Groebel’s recent work is much different than his older work, because he is making them in the present day instead of 1990, and he’s been consistently challenging himself the whole time. [16] The present is something that keeps slipping away.

We can skip a lot of obnoxious discourse if we really internalize that contemporary art looks the way it does because it’s being made right now, in the same way that Renaissance times art looks like that because it was made when and where it was, same for cave paintings, same for everything.

With that in mind, let’s ask, why is everyone painting the exact same things (pictures) the exact same way (passably) without any of these practices seeming to adhere together into a movement? Hell, even “post-internet” artists were getting token placements at the PS1 back in the day.

Here’s the thing: I don’t think this is an arts problem. Furthermore, I don’t think Tasneem Sarkez is much of an artist. I am aware of how alarming this sounds. I am going to spend the rest of this essay clarifying what I mean.

Let’s reaffirm that being an artist is not an exceptionally good or bad thing. Artist is a trade in a system of trades and an artwork is an object in a series of objects. An artwork is, by design, not a tool, so an artwork does not have revolutionary potential, but a healthy society will nourish its artists. It’s like how a healthy tree will bear fruit, though it will never taste the sweetness of its juice. This is to say that I am not arguing about whether or not given work ~is art~ in the way that stupid people recreationally argue about that sort of shit on the internet. Being a work of art is not an aspirational quality that is ascribed to an object that meets a standard of aesthetic and/or discursive rigor. Art is what people put in art galleries.

With that in mind, it is alarming to me how, at least in the States, each of our humanities have been rezoned to fit entirely within the university and the art gallery.

I’ve spent the last few years struggling to process Cameron Rowland’s work. Their piece Jim Crow has been on display at the Carnegie since I first moved to Pittsburgh. Here’s an image of the work, as well as the wall text that is required to be shown alongside this work:

Jim Crow, 2017

Jim Crow rail bender

36 × 7 ⅞ × 17 ⅜ inches (91.4 × 20 × 44 cm)

"Jim Crow is a racial slur, derived from the name of the minstrel character played by Thomas D. Rice in the 1830s. A Jim Crow is also a type of manual railroad rail bender. It has been referred to by this name in publications from 1870 to the present. The lease of ex-slave prisoners to private industry immediately following the Civil War is known as the convict lease system. Many of the first convict lease contracts were signed by railroad companies. Plessy v. Ferguson contested an 1890 Louisiana law segregating black railroad passengers. The Supreme Court upheld the law as constitutional. This created a precedent for laws mandating racial segregation, later to be known as Jim Crow laws."[17]

So, it looks like a Duchampian readymade, and it is a found object, but Jim Crow breaks from the readymade tradition in a few slight, but important ways. All of Duchamp’s readymades intend some sort of effect, be it aesthetic or intellectual, that was beyond the capacity of each object prior to Duchamp’s authorship of each object. Additionally, Duchamp produced readymades that were complex in format or otherwise difficult to understand at first glance, but the tools necessary to gain a thorough understanding of each of his readymades are always a part of the readymades themselves. You don’t need wall text with Duchamp in the way you do with Rowland.

Three Standard Stoppages is a useful example here. The rulers included with this work clarify that the work in question is not the strands of hair Duchamp has mounted to cloth, nor the rulers themselves, but the curved lines the strands of hair produced as they fell onto their strips of cloth.[18] The artist’s box containing Three Standard Stoppages contains the minimum number of objects necessary to convey this specific, complex idea.

In this way, Jim Crow fails as a Duchampian readymade. Not only does Rowland not necessarily expect you to know what to do with this object on your own, it is changed little as an object for contemplation due to its authorship by Rowland. It is still a piece of ephemera related to slavery. Here, Rowland has brought it to the attention of a new audience, and that is certainly a sort of work, but that on its own does not seem like a particularly interesting artistic process. Isn’t this work more fit for a history museum, not an art gallery?

Well, that’s the rub, ain’t it?

Last month, Rowland premiered a new work at Palais de Tokyo in Paris, titled Replacement, as part of the major survey Echo Delay Reverb: American Art, Francophone Thought. According to Palais de Tokyo, Echo Delay Reverb “explores the history of the transatlantic circulation of forms and ideas through the works of some sixty artists, bringing together a wide variety of mediums and a number of new commissions.”[19] Should be a perfect fit for Rowland! Here’s a couple images of Replacement, as well as the wall text that is required to be shown alongside this work (in this case, displayed in both French and English):

Replacement, 2025

Martinican flag

"The French flag [located above the front entrance to the building] is replaced by the flag of Martinique.

Since it was colonized by the French in 1635, Martinique has been a part of France. Martinique remains part of the French nation-state as an overseas department. France remains reliant on Martinique. Black Martinicans have pursued the end of French rule for 390 years"[20]

One day later, Maxwell Graham, the gallery representing Rowland, posted this statement:

“Palais de Tokyo has determined that Cameron Rowland’s artwork Replacement could be considered illegal. As a result it is no longer included in the exhibition.”[21]

This is out of the realm of how we define art. France’s governing body has decided that Cameron Rowland’s work isn’t art. If Replacement was a work of art, there would be no issue with this stunt. It is, legally, more praxis than art. Consequently, I have to agree with France on the status of Rowland's gesture, since they are a body that dictates which works enforce the liberal aperatus and which ones oppose it. The reason I’ve had so much trouble squaring Rowland’s cultural project is that it isn’t an art project at all, or at least, it is a project constantly teetering in and out of being art. Rowland is a historian, and their work is the encroachment of history of the perpetual now of the gallery space.

We must remember that the contemporary art gallery’s narcotic white walls were not at all standardized until very, very recently. The white cube’s primary purpose in the present day, now that the modernist project it was initially designed for has shifted into the rearview, is to instill a space with a self-referential sense of gallery-ness, so that the work within may similarly arrive pre-aestheticized. It is nostalgic in the same way that airbrush paintings of childhood ephemera are nostalgic.

My gut reaction when I see a painting by Tasneem Sarkez or Julia De Ruiter is “damn I wish you were just showing me your reference materials instead of these paintings,” followed shortly after by “damn, I really wish you had written an essay about this instead. That would’ve been a lot more cohesive.” But, isn’t that just a polite way of kicking these works out of the public eye? We can say that Cameron Rowland’s work would be better fit for a history museum, but, where is the history museum that would stage their work?

American arts infrastructure is negligible, but anywhere you go here, if you dig for it, you’ll find some sort of DIY, youth led arts scene. This is not so true of any of the other humanities. When a history organization wants to host their work in a physical space, they will either have to appease our most heavily policed and intensely politicized arbiters of knowledge (those institutions that protect their confederate monuments more than the lives of their civilian populus), or temporarily squat in spaces not designed for them. There are no spaces for people’s histories in America in the way there are spaces for people’s art. This may be because history is dangerous in a way art is not. Ditto for philosophy, theology, so on.

The confederate statue is actually a perfect example of a historic object that is protected by the liberal apparatus by being erroneously labeled as an artistic object. It contains art, but art is not its primary function. These are the sort of objects Rowland is producing.

All of the bad parts of Tasneem Sarkez’s work are the parts that are the art. The way she extrapolates on her lived history is interesting and current, but for people to come to the opening, she has to paint a picture. If a movement emerges from between our current picture-painters, it will not be in the arts. There is fertile ground for authored, deinstitutionalized public venues for the humanities with rotating exhibitions and a similar infrastructure to the house venues omnipresent in DIY spaces. The desire for these spaces is bleeding from every attempt to sign someone else’s name onto a found photograph.

The closest space I can think of to the sort of space I’m imagining is carriage trade, an institution running continuously in Manhattan since 2008. They’re an arts space, and their shows are art shows, but unlike virtually every other space in New York, they are not primarily interested in newness. Each of their shows is a rigorously curated survey of a singular theme or project, often relating to American history.

The work shown in carriage trade is rarely presented neutrally, and is often shown under a decidedly critical lens (can you imagine?!). For instance, Rich Land, Poor Land contrasted commissioned documentary photographs of California’s World War II-era Japanese concentration camps by both Dorothea Lange and Ansel Adams.[22] For his part, Adams was much more interested in photographing the mountains behind the camps than the camps themselves. His passion for natural forms made him a perfect vehicle for propaganda.

carriage trade’s only shows composed entirely of recent works produced with the gallery in mind are part of their Social Photography series. Running regularly since 2011,[23] with its 11th installment opening in 2025,[24] the photographs in these shows are all taken on consumer grade cell phones and sold as small format prints at a low price point. Besides being an effective fundraiser for the gallery, and besides it producing some great works of art, Social Photography’s prescient topic, open-ended parameters, and rigorous consistency have yielded a singular survey of two decades of mundanity. It is a sort of history that our state institutions are generally not keen on producing.

The worst moments at carriage trade can feel pretty preachy (the least successful components of their shows are generally newer works that veer on the side of art), but I can think of no other independent spaces that is performing the crucial work of untangling our art from the malaise of the white cube. But, carriage trade is still an arts space, and its primary focus is tracking the way images proliferate. This is not to its detriment, of course, but I’d say that carriage trade has only survived as long as it has because it’s been able to smuggle its way onto ArtGuide.

There is a place for history in the arts, of course, but as of now, there is no place for the arts in history. Refusing to play to the gallery will make your work better, but it will often mean galleries will not show your work. When we are working with personal histories, home videos, anything of the sort, we shouldn’t ask if this is art. Of course it’s art. It’s in an art gallery. We must instead ask, removed from all hostile discourses, “should this be art?” Should it be stripped of some of its context in service of aesthetic clarity? If it shouldn’t, you should make a place for it to go. This is part of being good to your work. And if you look to your photo-painting practice and see no such history, look closer.

Patrick Totally's website

Footnotes

[1]